Welcome back, forks! After a long period of not posting here, I am happy to share that I am back again on MIB. In this post, we will work on an end-to-end machine learning project. I firmly believe this is one of the most detailed and comprehensive end-to-end ML project blog post on the internet. This project is perfect for the beginner in Machine Learning and seasoned ML engineers who could still learn one or two things from this post. This project was featured on Luke Barousse Youtube channel, click here to watch the video.

Here is the roadmap we will follow:

- We will start with exploratory data analysis(EDA)

- Feature engineering

- Feature selection

- Data preprocessing

- Model training

- Model selection

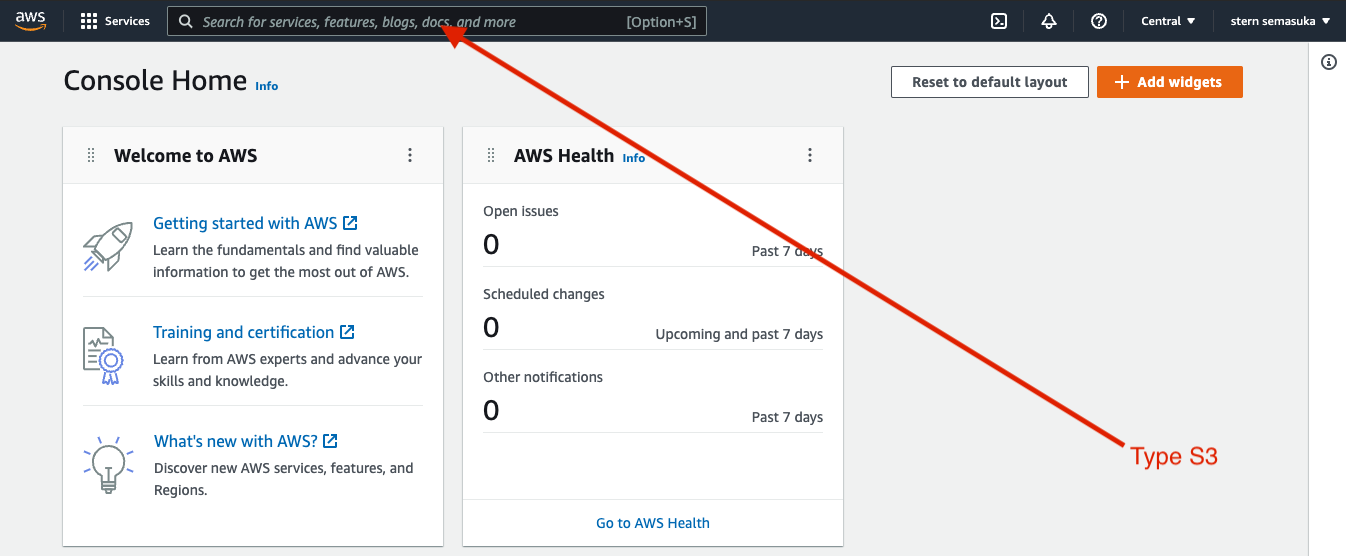

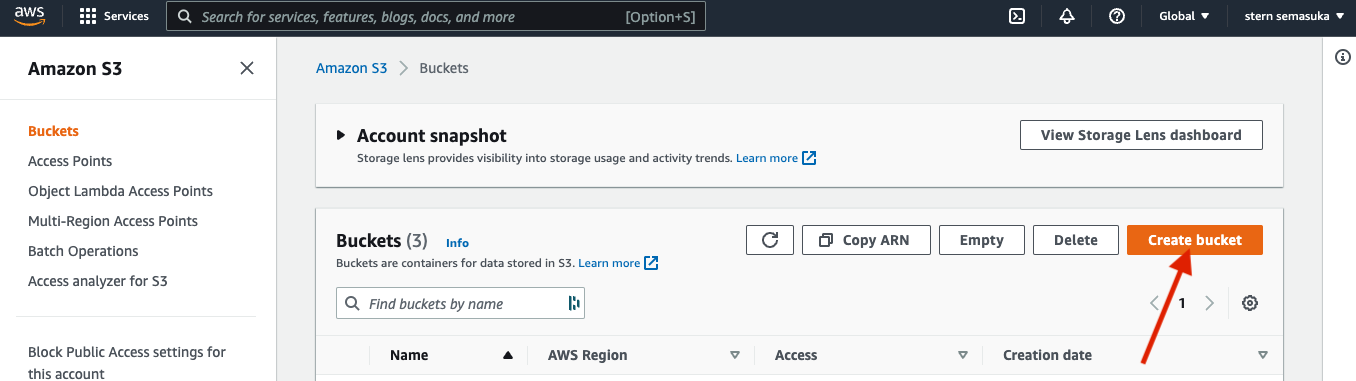

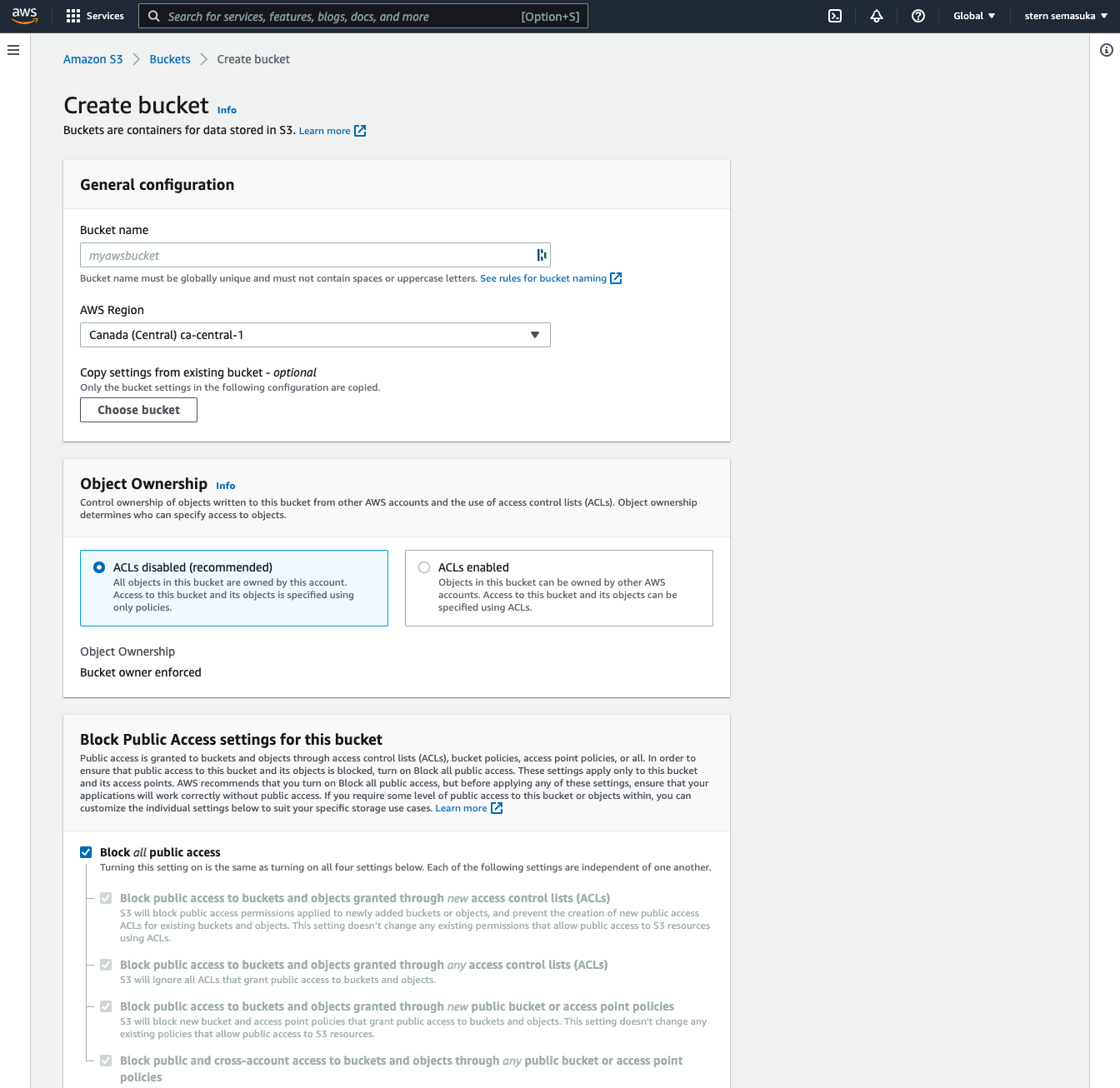

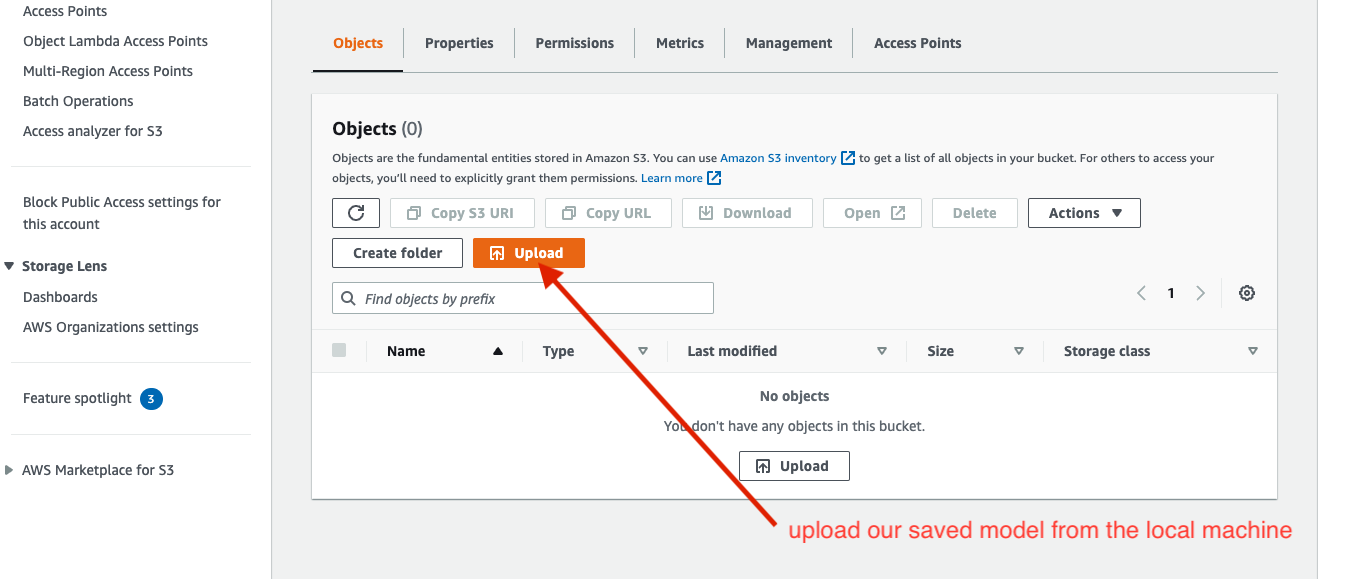

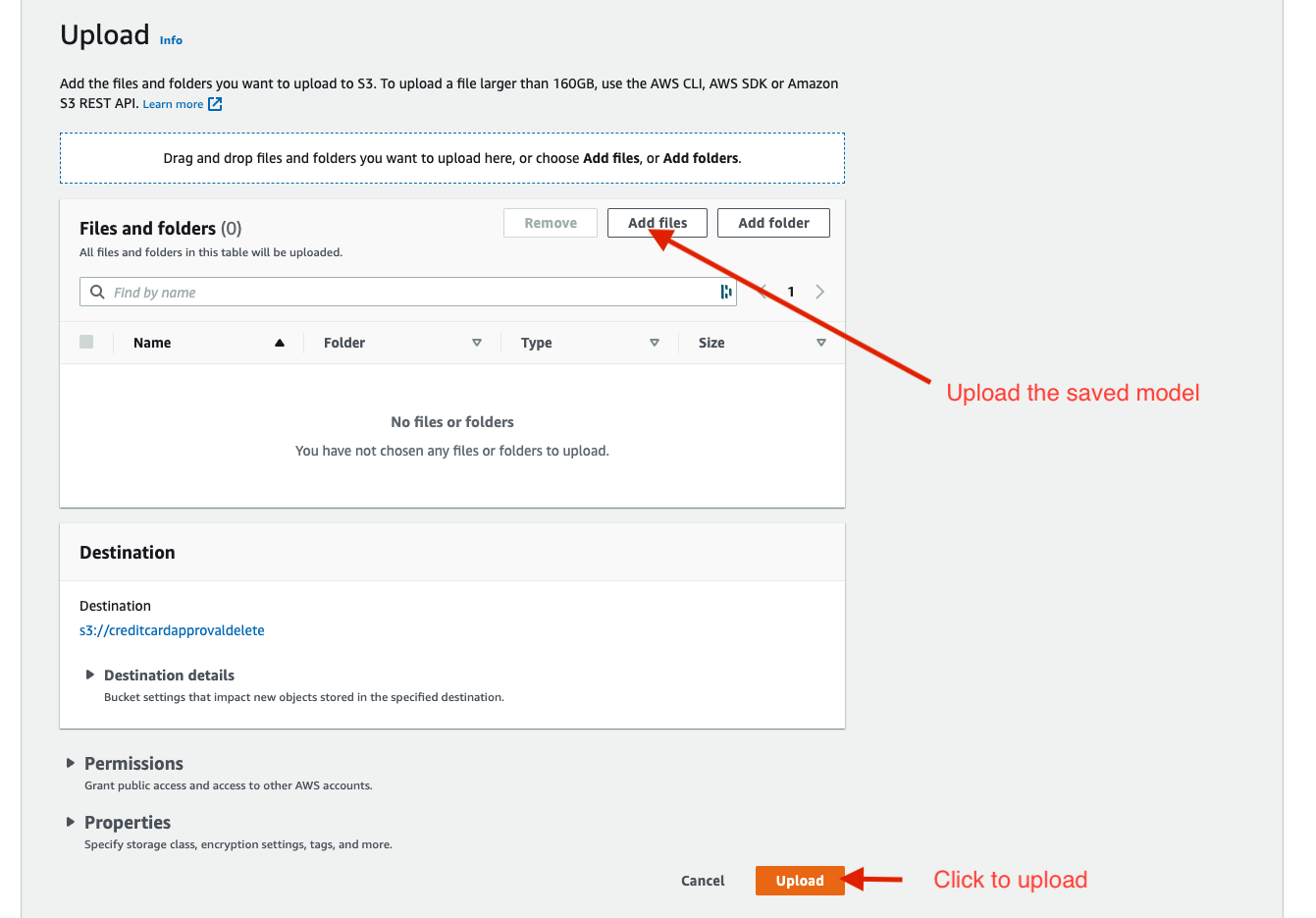

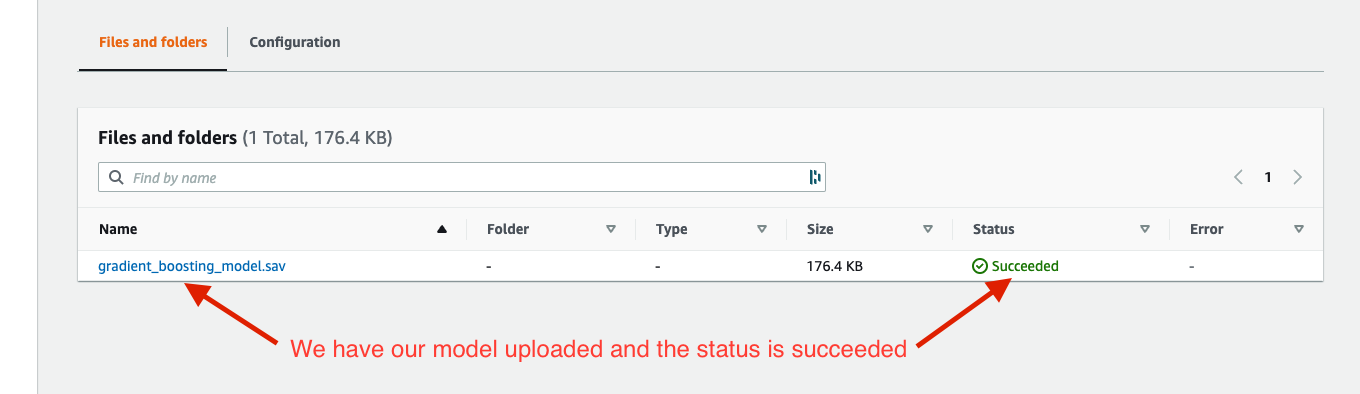

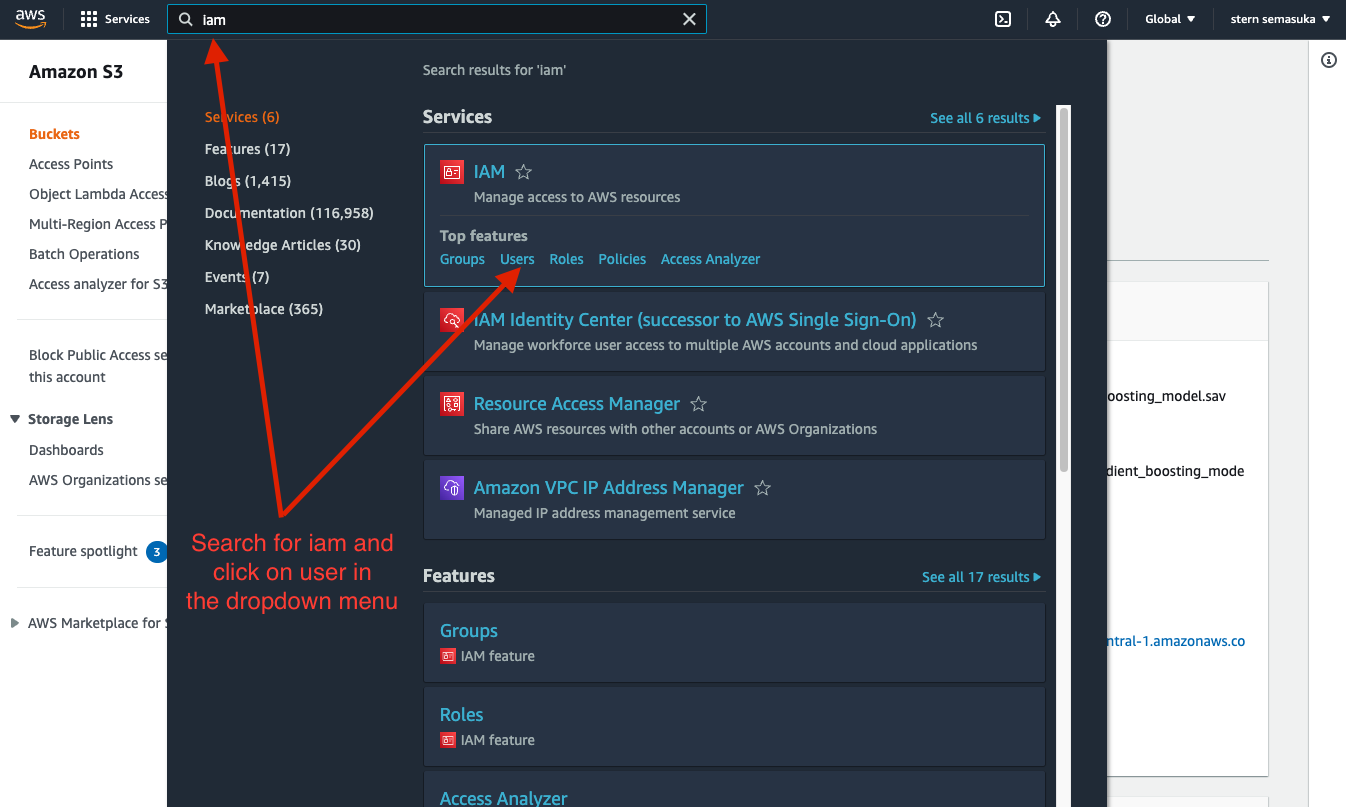

- Model storage on AWS blob storage

- Build a web app interface for the model using Streamlit.

- Finally, deploy the model.

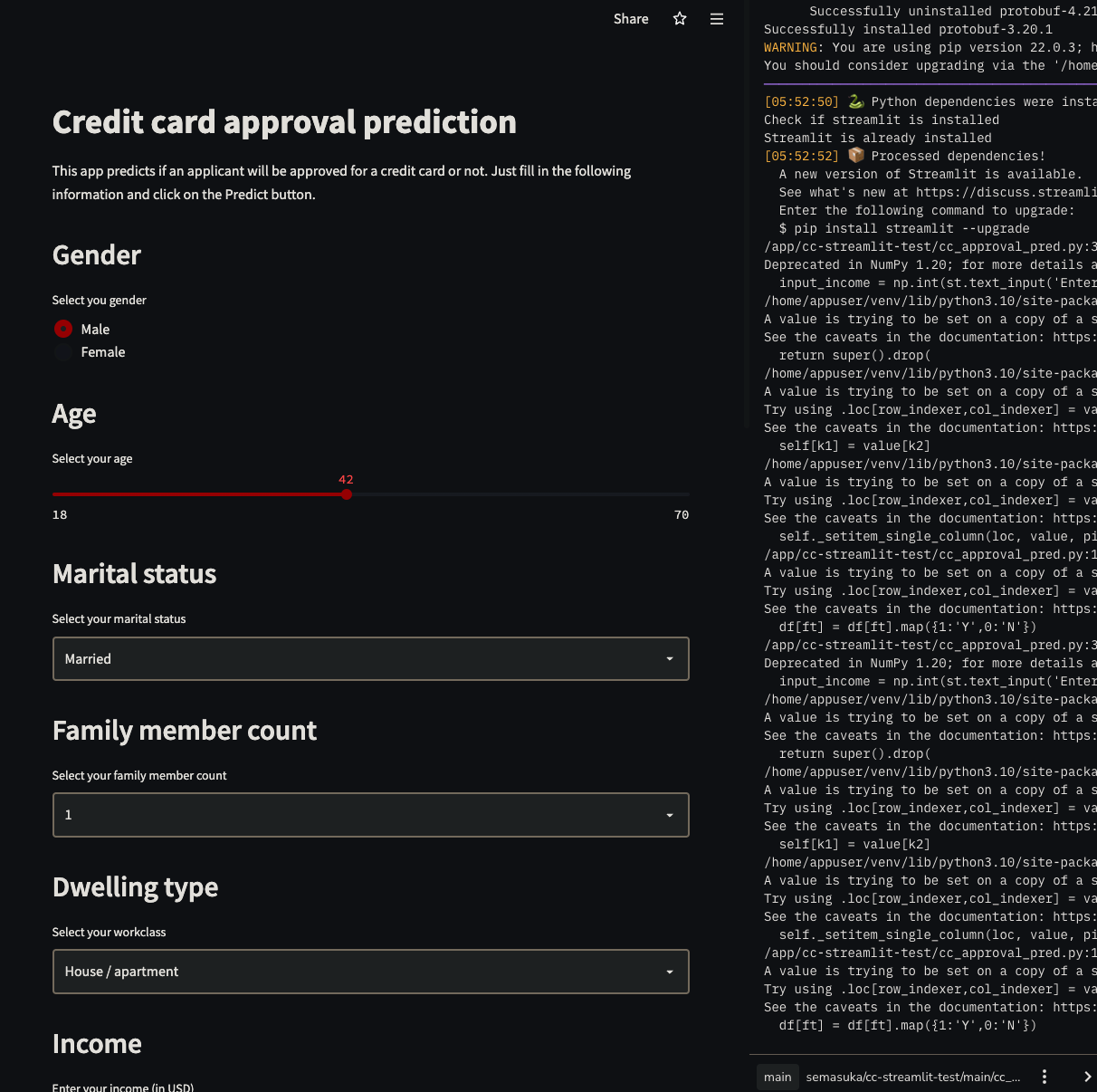

The goal is to predict whether an application for a credit card will be approved or not, using the applicant data.

I chose this project because when applying for a loan, credit card, or any other type of credit at any financial institution, there is a hard inquiry that affects your credit score negatively. This app predicts the probability of being approved without affecting your credit score. This app can be used by applicants who want to find out if they will be approved for a credit card without affecting their credit score.

For those who are in a hurry, here is the key insights results from the analysis of this project:

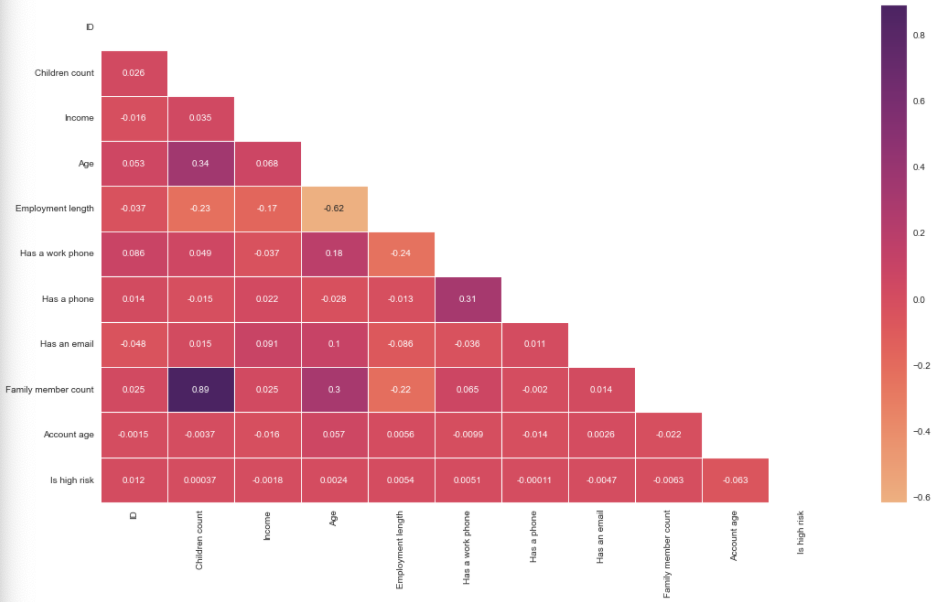

Correlation between the features.

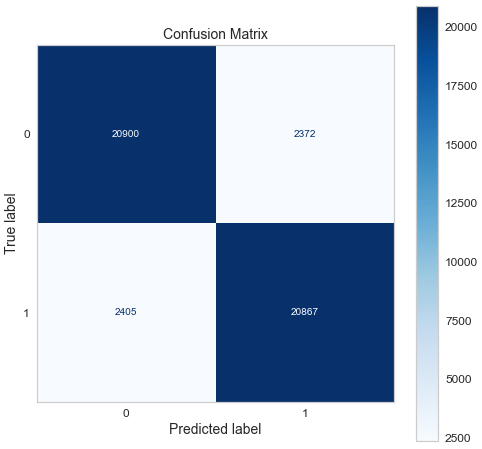

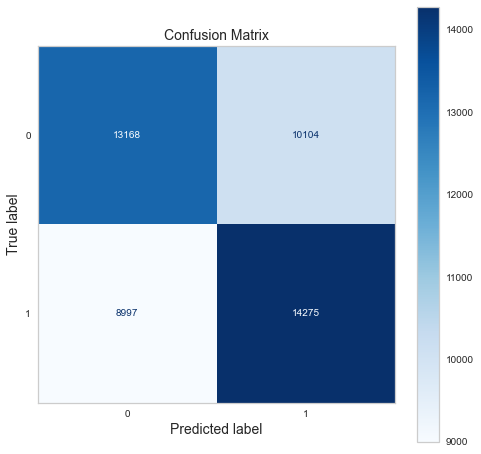

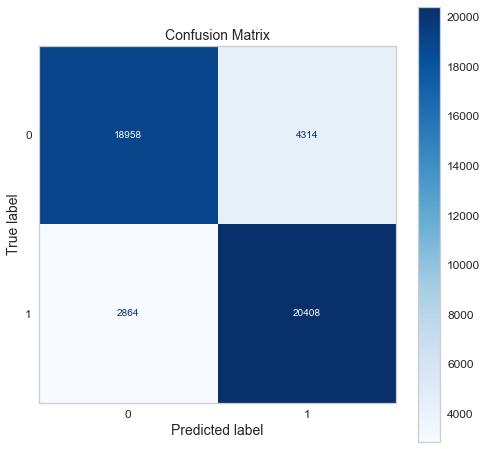

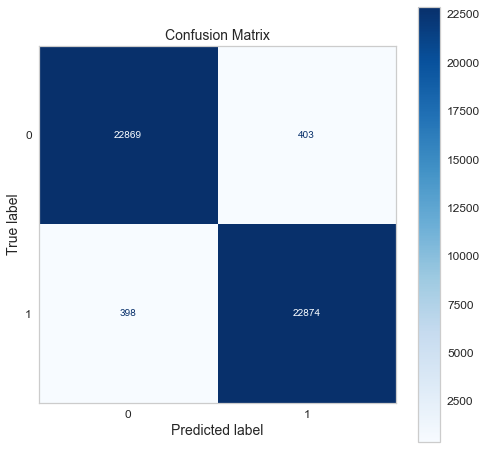

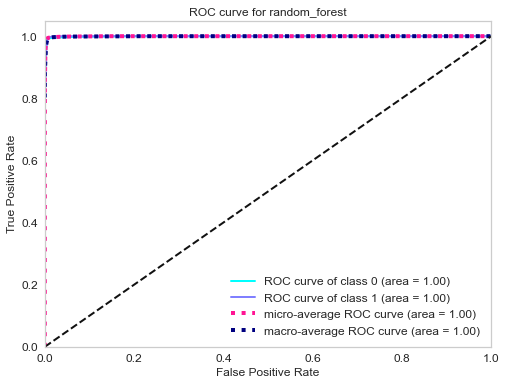

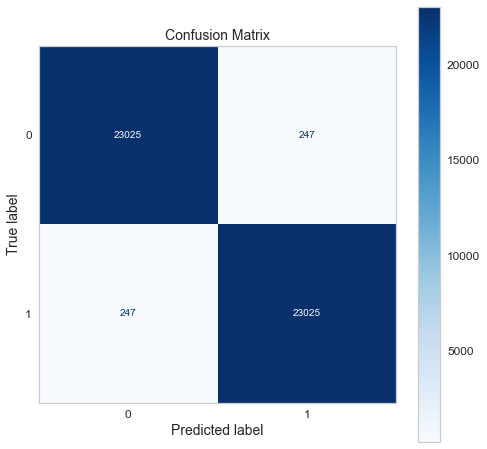

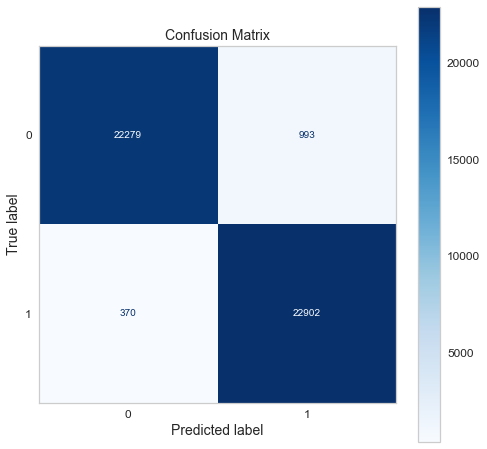

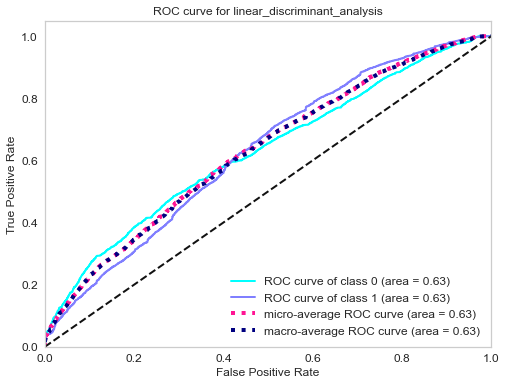

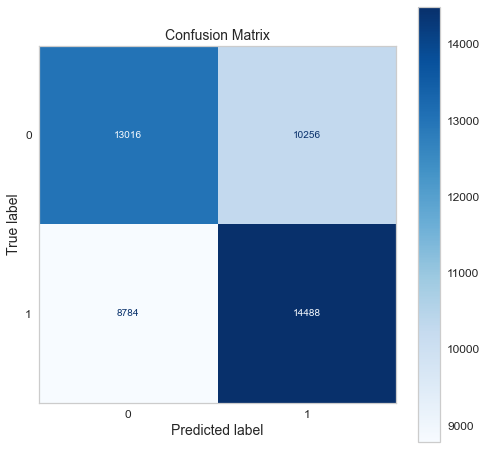

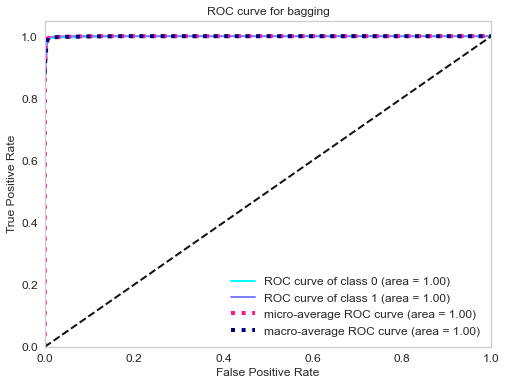

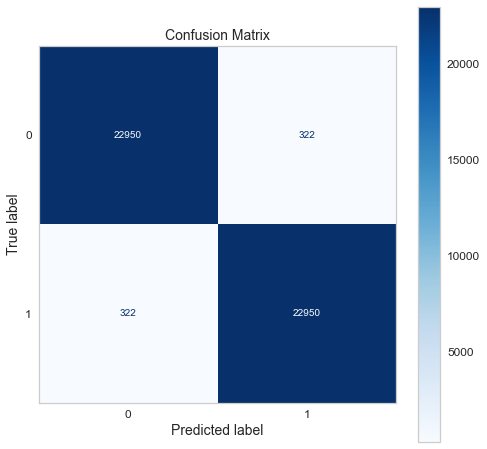

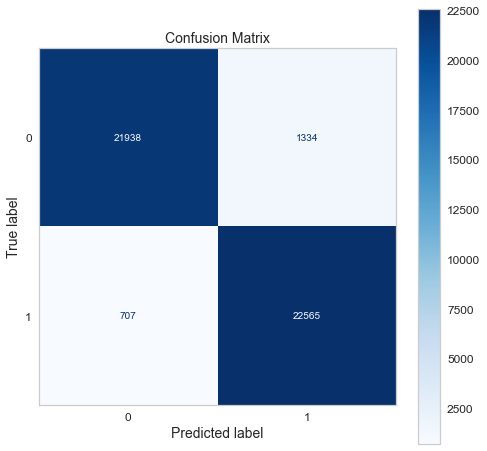

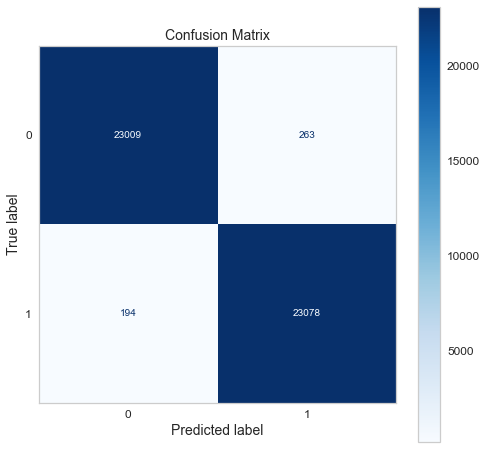

Confusion matrix of gradient boosting classifier.

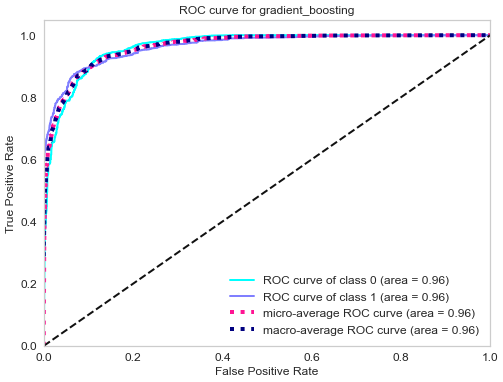

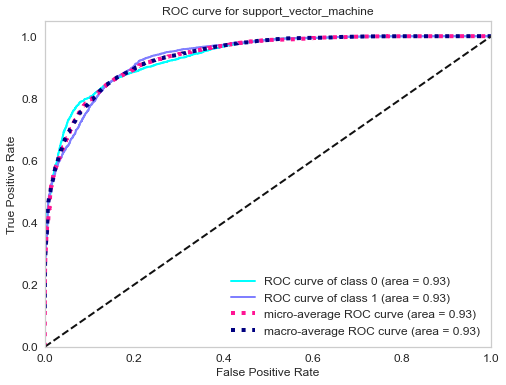

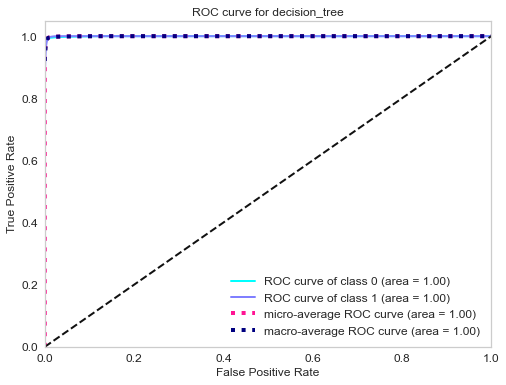

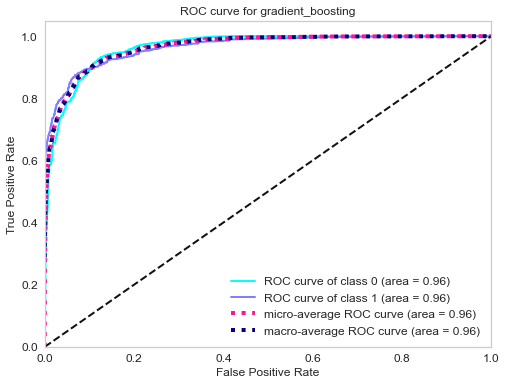

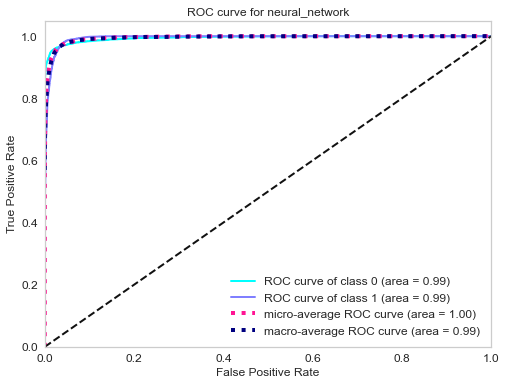

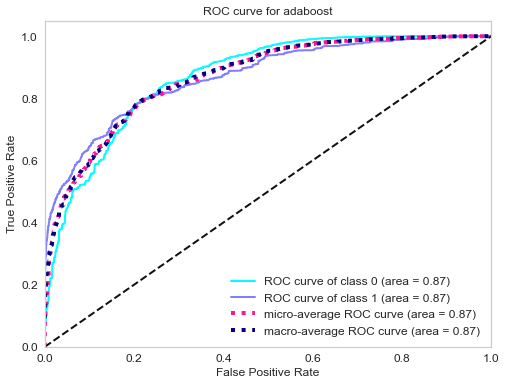

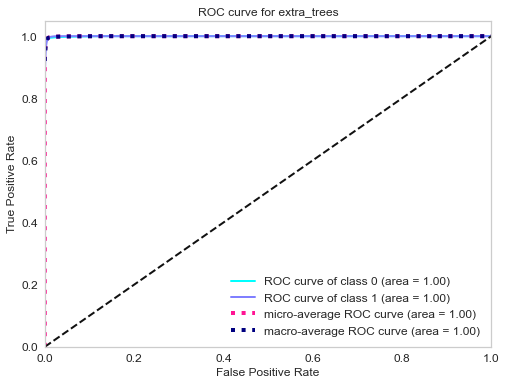

ROC curve of gradient boosting classifier.

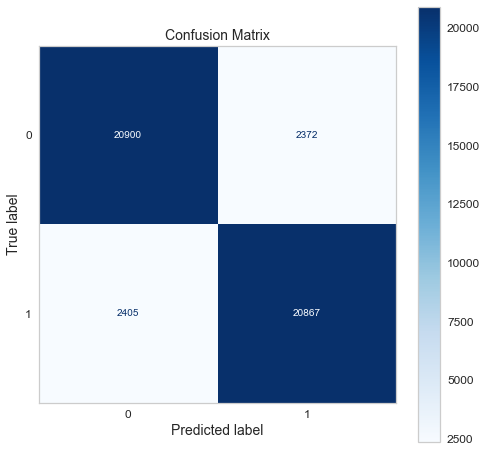

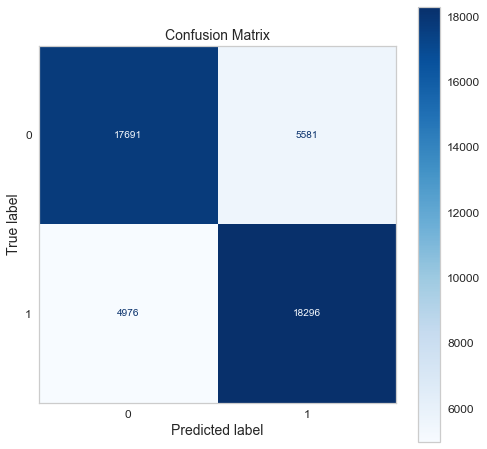

Top 3 models (with default parameters)

| Model | Recall score |

|---|---|

| Support vector machine | 88% |

| Gradient boosting | 90% |

| Adaboost | 79% |

- The final model used for this project: Gradient boosting

- Metrics used: Recall

-

Why choose recall as metrics: Since the objective of this problem is to minimize the risk of a credit default, the metrics to use depends on the current economic situation:

-

During a bull market (when the economy is expanding), people feel wealthy and are employed. Money is usually cheap, and the risk of default is low because of economic stability and low unemployment. The financial institution can handle the risk of default; therefore, it is not very strict about giving credit. The financial institution can handle some bad clients as long as most credit card owners are good clients (aka those who pay back their credit in time and in total).In this case, having a good recall (sensitivity) is ideal.

-

During a bear market (when the economy is contracting), people lose their jobs and money through the stock market and other investment venues. Many people struggle to meet their financial obligations. The financial institution, therefore, tends to be more conservative in giving out credit or loans. The financial institution can’t afford to give out credit to many clients who won’t be able to pay back their credit. The financial institution would rather have a smaller number of good clients, even if it means that some good clients are denied credit. In this case, having a good precision (specificity) is desirable.

Note: There is always a trade-off between precision and recall. Choosing the right metrics depends on the problem you are solving.

Conclusion: Since the time I worked on this project (beginning 2022), we were in the longest bull market (excluding March 2020 flash crash) ever recorded; we will use recall as our metric.

-

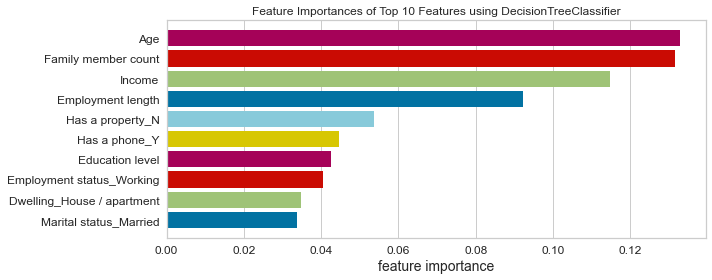

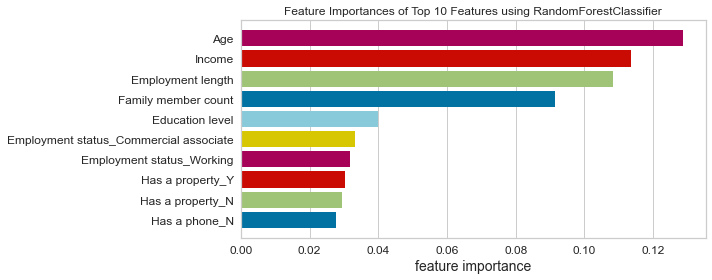

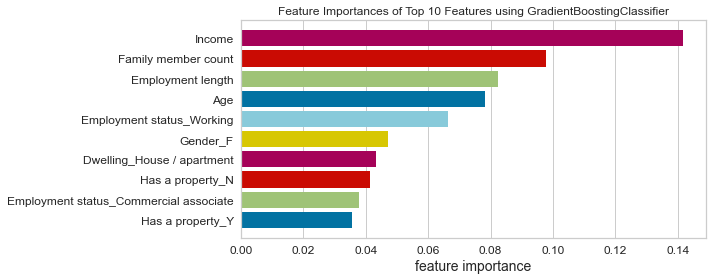

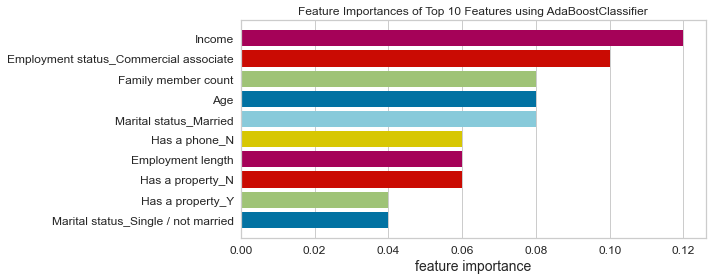

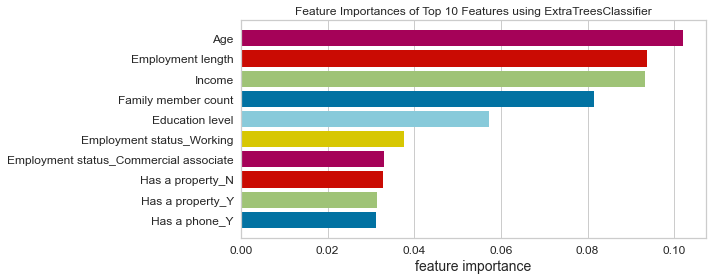

Lessons learned and recommendation

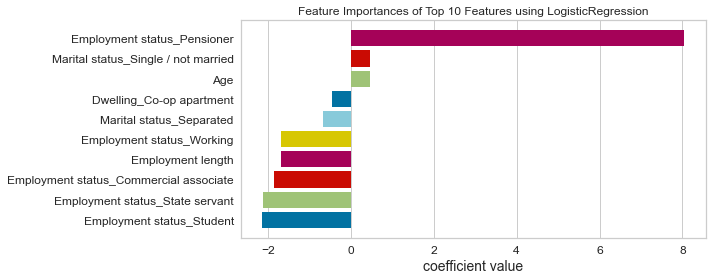

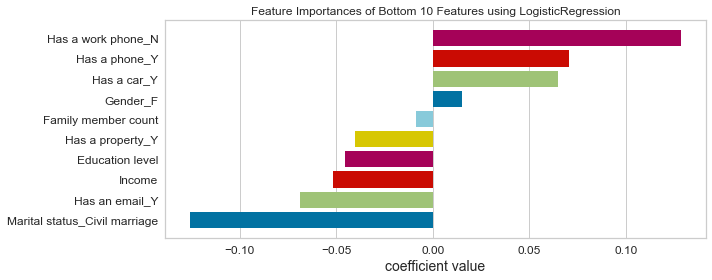

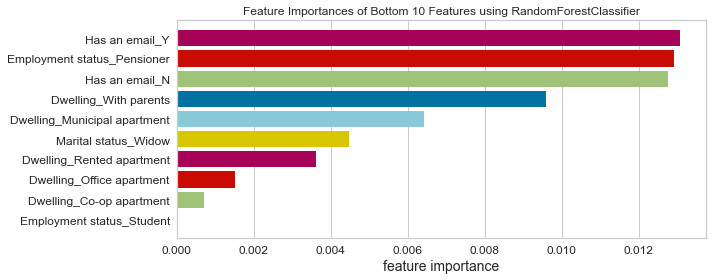

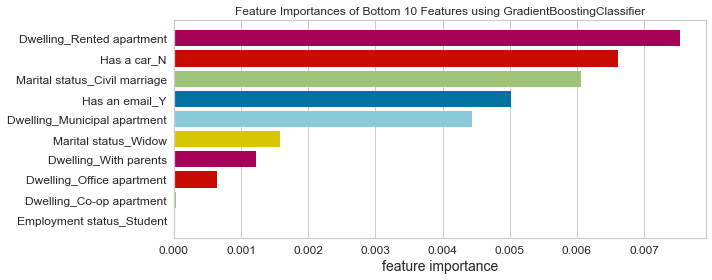

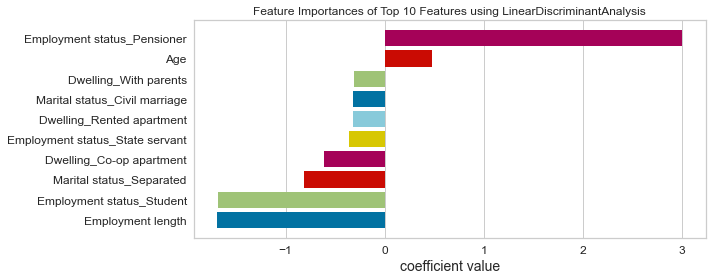

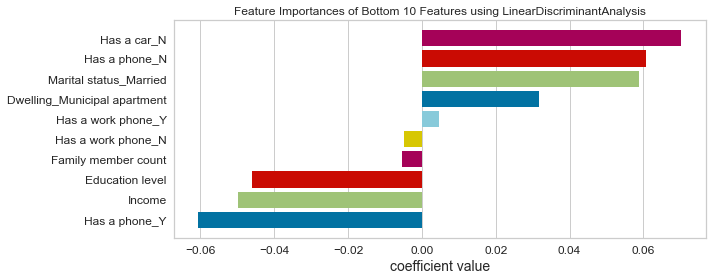

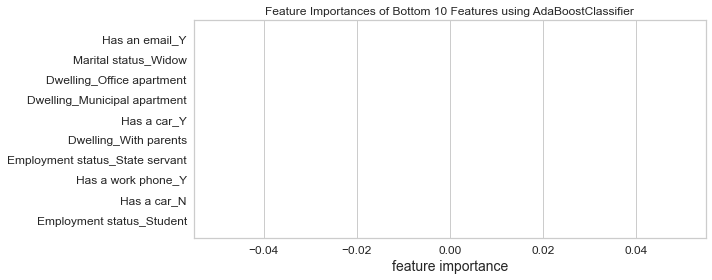

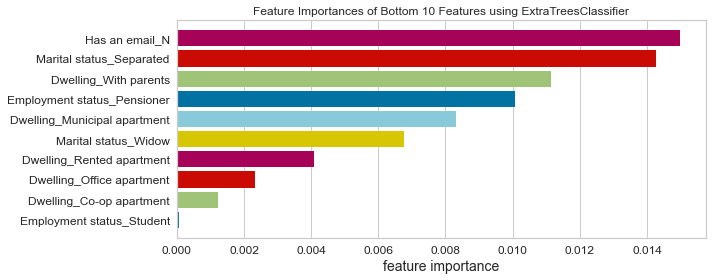

- Based on this project’s analysis, income, family member headcount, and employment length are the three most predictive features in determining whether an applicant will be approved for a credit card. Other features like age and working employment status are also helpful. The least useful features are the type of dwelling and car ownership.

- The recommendation would be to focus more on the most predictive features when looking at the applicant profile and pay less attention to the least predictive features.

For the rest of my nerdy friends, let’s get started from scratch

Pre-requisites

Wait! no, so fast! Before we start writing code, we need to have our python/jupyter environment ready, and Ken Jee has a fantastic video on this; click here to watch it.

Import necessary libraries

Now we can import all the required libraries. Feel free to visit my other post, where I talk about installing these libraries in the jupyter environment.

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import missingno as msno

import matplotlib

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import seaborn as sns

import warnings

from pandas.core.common import SettingWithCopyWarning

from pathlib import Path

from scipy.stats import probplot, chi2_contingency, chi2, stats

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split, GridSearchCV, RandomizedSearchCV, cross_val_score, cross_val_predict

from sklearn.base import BaseEstimator, TransformerMixin

from sklearn.pipeline import Pipeline

from sklearn.calibration import CalibratedClassifierCV

from sklearn.compose import ColumnTransformer

from sklearn.preprocessing import OneHotEncoder, MinMaxScaler, OrdinalEncoder

from sklearn.metrics import ConfusionMatrixDisplay, classification_report, roc_curve, roc_auc_score

from imblearn.over_sampling import SMOTE

from sklearn.linear_model import SGDClassifier, LogisticRegression

from sklearn.svm import SVC

from sklearn.tree import DecisionTreeClassifier

from sklearn.ensemble import RandomForestClassifier, GradientBoostingClassifier, BaggingClassifier, AdaBoostClassifier, ExtraTreesClassifier

from sklearn.naive_bayes import GaussianNB

from sklearn.neighbors import KNeighborsClassifier

from sklearn.discriminant_analysis import LinearDiscriminantAnalysis

from sklearn.neural_network import MLPClassifier

from sklearn.inspection import permutation_importance

import scikitplot as skplt

from yellowbrick.model_selection import FeatureImportances

import joblib

import os

%matplotlib inline

I will briefly explain what each library does and why we need it for this project.

- NumPy is a library for manipulating multidimensional arrays and matrices. In this project, we will use NumPy to change the sequences of the elements in a list and also transform an array with negative values into absolute ones.

- Pandas is a library to manipulate tabular data stored as dataframes (More than two columns) and Series(when dealing with one column); we will use it in this project to import the data into our notebook, create dataframes, merge and concatenate dataframes.

- MissingNo is a great library to visualize at a glance missing value in a Pandas dataframe.

- Scipy is a library that contains mathematical modules like statistics, optimization, linear algebra, etc

- Pathlib is a built-in python library with useful path functionalities. Pathlib will use it in the project to check if a file exists at a specific path, then use the joblib to save it.

- Matplotlib is a data visualization library to plot different types of plots like histograms, line plots, scatter plots, contour plots, etc. It is built on top of NumPy.

- Seaborn is another data visualization library built on top of Matplotlib with added features and simpler syntax than Matplotlib. We will mainly use this library for our exploratory data analysis.

- Warnings is a python builtin library to control the warnings at the execution time

- Scikit-learn, also called sklearn, is the industry standard machine learning library from which all the machine learning algorithms are imported. It is built on NumPy, Scipy, and Matplotlib.

- Imbalance learn is a library based on sklearn, which provides tools when dealing with classification with imbalanced classes. Here classes mean the prediction results, which in this case, are approved or denied for a credit card. In this project, we have two outcomes (we have a binary classification), and one of the outcomes is less likely to happen, which is reflected in the data. So we use the SMOTE technique to balance the outcomes because we don’t want to train on unbalanced data as we try to avoid bias.

- Scikit-plot is a helpful library that plots scikit-learn objects; for this project, Scikit-plot will use to plot the ROC curve.

- Yellowbrick extends the scikit-learn API library to make a model selection. In this project, we have used it to plot the feature importance.

- Joblib is a builtin python library to save models as files; those models will deploy on AWS S3

- os is a builtin library to access some of the operating system functionality

- Finally, magic command

%matplotlib inlinewill make your plot outputs appear and be stored within the notebook.

Import the data

After importing the libraries, we will now import the datasets. The datasets are from Kaggle. Here is the link.

There are two ways to import the CSV, we can download the file and pass the local machine path to the read_csv pandas function, or we can host the data on GitHub and directly read the hosted CSV file as a raw data. In this case, we went with the latter method.

The first dataset is the application record with all the information about the applicants like gender, age, income, etc. The second dataset is the credit record which holds information about the credit status and balance. we will store those two dataset in cc_data_full_data and credit_status respectively.

cc_data_full_data = pd.read_csv('https://raw.githubusercontent.com/semasuka/Credit-card-approval-prediction-classification/main/datasets/application_record.csv')

credit_status = pd.read_csv('https://raw.githubusercontent.com/semasuka/Credit-card-approval-prediction-classification/main/datasets/credit_record.csv')

Let’s glance at the first five rows using each Pandas’ head` method.

cc_data_full_data.head()

| ID | CODE_GENDER | FLAG_OWN_CAR | FLAG_OWN_REALTY | CNT_CHILDREN | AMT_INCOME_TOTAL | NAME_INCOME_TYPE | NAME_EDUCATION_TYPE | NAME_FAMILY_STATUS | NAME_HOUSING_TYPE | DAYS_BIRTH | DAYS_EMPLOYED | FLAG_MOBIL | FLAG_WORK_PHONE | FLAG_PHONE | FLAG_EMAIL | OCCUPATION_TYPE | CNT_FAM_MEMBERS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 5008804 | M | Y | Y | 0 | 427500.0 | Working | Higher education | Civil marriage | Rented apartment | -12005 | -4542 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | NaN | 2.0 |

| 1 | 5008805 | M | Y | Y | 0 | 427500.0 | Working | Higher education | Civil marriage | Rented apartment | -12005 | -4542 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | NaN | 2.0 |

| 2 | 5008806 | M | Y | Y | 0 | 112500.0 | Working | Secondary / secondary special | Married | House / apartment | -21474 | -1134 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Security staff | 2.0 |

| 3 | 5008808 | F | N | Y | 0 | 270000.0 | Commercial associate | Secondary / secondary special | Single / not married | House / apartment | -19110 | -3051 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | Sales staff | 1.0 |

| 4 | 5008809 | F | N | Y | 0 | 270000.0 | Commercial associate | Secondary / secondary special | Single / not married | House / apartment | -19110 | -3051 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | Sales staff | 1.0 |

credit_status.head()

| ID | MONTHS_BALANCE | STATUS | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 5001711 | 0 | X |

| 1 | 5001711 | -1 | 0 |

| 2 | 5001711 | -2 | 0 |

| 3 | 5001711 | -3 | 0 |

| 4 | 5001712 | 0 | C |

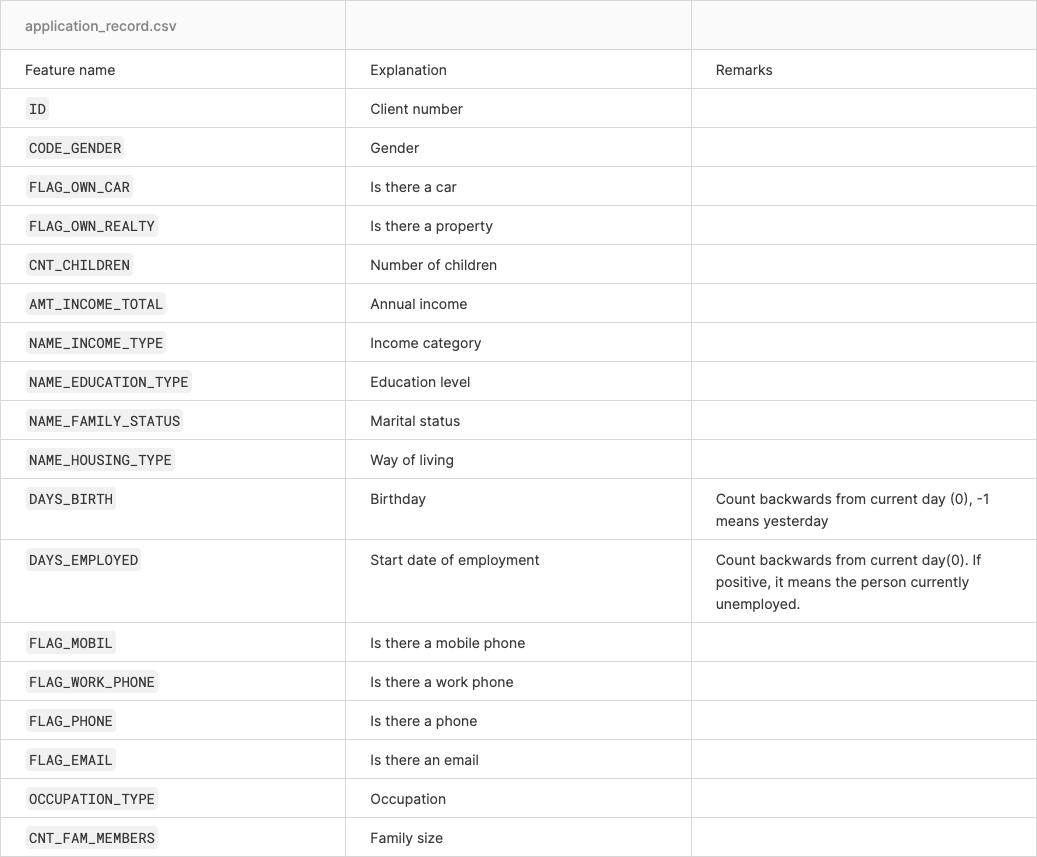

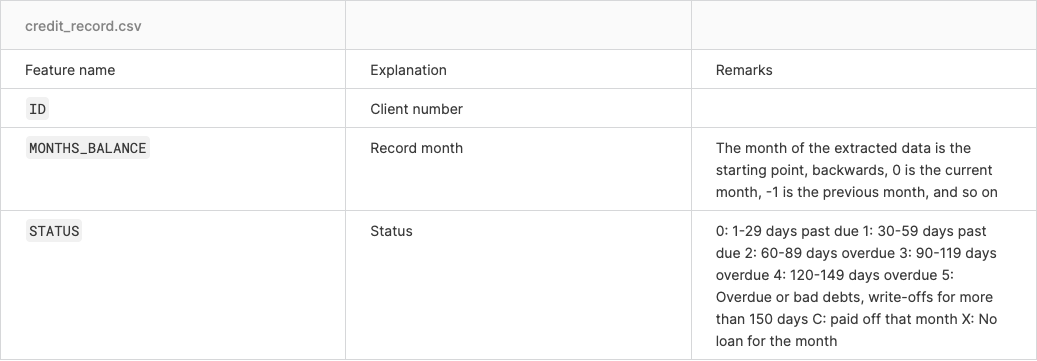

Now let’s look at the metadata of the datasets to understand the data better.

For the application record dataset.

And for the credit record dataset.

Creating a target variable

As you may have noticed from our first dataset, we don’t have a target variable that states whether the client is good or not (a client who will not default on their credit card would be called a good client). We will use the credit record to come up with the target variable. We use the vintage analysis for this.

For simplicity purposes, we will say that the applicants over 60 days overdue are considered bad clients. When the target variable is 1, that means a bad client, and when it is 0, that represents a good client. That is what the following script does.

begin_month=pd.DataFrame(credit_status.groupby(['ID'])['MONTHS_BALANCE'].agg(min))

begin_month=begin_month.rename(columns={'MONTHS_BALANCE':'Account age'})

cc_data_full_data=pd.merge(cc_data_full_data,begin_month,how='left',on='ID')

credit_status['dep_value'] = None

credit_status['dep_value'][credit_status['STATUS'] =='2']='Yes'

credit_status['dep_value'][credit_status['STATUS'] =='3']='Yes'

credit_status['dep_value'][credit_status['STATUS'] =='4']='Yes'

credit_status['dep_value'][credit_status['STATUS'] =='5']='Yes'

cpunt=credit_status.groupby('ID').count()

cpunt['dep_value'][cpunt['dep_value'] > 0]='Yes'

cpunt['dep_value'][cpunt['dep_value'] == 0]='No'

cpunt = cpunt[['dep_value']]

cc_data_full_data = pd.merge(cc_data_full_data,cpunt,how='inner',on='ID')

cc_data_full_data['Is high risk']=cc_data_full_data['dep_value']

cc_data_full_data.loc[cc_data_full_data['Is high risk']=='Yes','Is high risk']=1

cc_data_full_data.loc[cc_data_full_data['Is high risk']=='No','Is high risk']=0

cc_data_full_data.drop('dep_value',axis=1,inplace=True)

pd.options.mode.chained_assignment = None # hide warning SettingWithCopyWarning

/var/folders/bb/dzx22n7n1t1gkqfhhky4j2ch0000gn/T/ipykernel_29855/1467211908.py:5: SettingWithCopyWarning:

A value is trying to be set on a copy of a slice from a DataFrame

See the caveats in the documentation: https://pandas.pydata.org/pandas-docs/stable/user_guide/indexing.html#returning-a-view-versus-a-copy

credit_status['dep_value'][credit_status['STATUS'] =='2']='Yes'

/var/folders/bb/dzx22n7n1t1gkqfhhky4j2ch0000gn/T/ipykernel_29855/1467211908.py:6: SettingWithCopyWarning:

A value is trying to be set on a copy of a slice from a DataFrame

See the caveats in the documentation: https://pandas.pydata.org/pandas-docs/stable/user_guide/indexing.html#returning-a-view-versus-a-copy

credit_status['dep_value'][credit_status['STATUS'] =='3']='Yes'

/var/folders/bb/dzx22n7n1t1gkqfhhky4j2ch0000gn/T/ipykernel_29855/1467211908.py:7: SettingWithCopyWarning:

A value is trying to be set on a copy of a slice from a DataFrame

See the caveats in the documentation: https://pandas.pydata.org/pandas-docs/stable/user_guide/indexing.html#returning-a-view-versus-a-copy

credit_status['dep_value'][credit_status['STATUS'] =='4']='Yes'

/var/folders/bb/dzx22n7n1t1gkqfhhky4j2ch0000gn/T/ipykernel_29855/1467211908.py:8: SettingWithCopyWarning:

A value is trying to be set on a copy of a slice from a DataFrame

See the caveats in the documentation: https://pandas.pydata.org/pandas-docs/stable/user_guide/indexing.html#returning-a-view-versus-a-copy

credit_status['dep_value'][credit_status['STATUS'] =='5']='Yes'

Let’s print the first 5 rows of the dataframe, with the newly created target column Is high risk at the end.

cc_data_full_data.head()

| ID | CODE_GENDER | FLAG_OWN_CAR | FLAG_OWN_REALTY | CNT_CHILDREN | AMT_INCOME_TOTAL | NAME_INCOME_TYPE | NAME_EDUCATION_TYPE | NAME_FAMILY_STATUS | NAME_HOUSING_TYPE | DAYS_BIRTH | DAYS_EMPLOYED | FLAG_MOBIL | FLAG_WORK_PHONE | FLAG_PHONE | FLAG_EMAIL | OCCUPATION_TYPE | CNT_FAM_MEMBERS | Account age | Is high risk | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 5008804 | M | Y | Y | 0 | 427500.0 | Working | Higher education | Civil marriage | Rented apartment | -12005 | -4542 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | NaN | 2.0 | -15.0 | 0 |

| 1 | 5008805 | M | Y | Y | 0 | 427500.0 | Working | Higher education | Civil marriage | Rented apartment | -12005 | -4542 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | NaN | 2.0 | -14.0 | 0 |

| 2 | 5008806 | M | Y | Y | 0 | 112500.0 | Working | Secondary / secondary special | Married | House / apartment | -21474 | -1134 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Security staff | 2.0 | -29.0 | 0 |

| 3 | 5008808 | F | N | Y | 0 | 270000.0 | Commercial associate | Secondary / secondary special | Single / not married | House / apartment | -19110 | -3051 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | Sales staff | 1.0 | -4.0 | 0 |

| 4 | 5008809 | F | N | Y | 0 | 270000.0 | Commercial associate | Secondary / secondary special | Single / not married | House / apartment | -19110 | -3051 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | Sales staff | 1.0 | -26.0 | 0 |

Since the features (columns) names are not very descriptive, we will change them to make them more readable.

# rename the features to more readable feature names

cc_data_full_data = cc_data_full_data.rename(columns={

'CODE_GENDER':'Gender',

'FLAG_OWN_CAR':'Has a car',

'FLAG_OWN_REALTY':'Has a property',

'CNT_CHILDREN':'Children count',

'AMT_INCOME_TOTAL':'Income',

'NAME_INCOME_TYPE':'Employment status',

'NAME_EDUCATION_TYPE':'Education level',

'NAME_FAMILY_STATUS':'Marital status',

'NAME_HOUSING_TYPE':'Dwelling',

'DAYS_BIRTH':'Age',

'DAYS_EMPLOYED': 'Employment length',

'FLAG_MOBIL': 'Has a mobile phone',

'FLAG_WORK_PHONE': 'Has a work phone',

'FLAG_PHONE': 'Has a phone',

'FLAG_EMAIL': 'Has an email',

'OCCUPATION_TYPE': 'Job title',

'CNT_FAM_MEMBERS': 'Family member count',

'Account age': 'Account age'

})

Now we will split the cc_data_full_data into a training and testing set. We will use 80% of the data for training and 20% for testing and store them respectively in cc_train_original and cc_test_original variables.

# split the data into train and test dataset

def data_split(df, test_size):

train_df, test_df = train_test_split(df, test_size=test_size, random_state=42)

# reset the indexes

return train_df.reset_index(drop=True), test_df.reset_index(drop=True)

# we set the test_size to 0.2, which means that the train_size will be 0.8

cc_train_original, cc_test_original = data_split(cc_data_full_data, 0.2)

Dataframe’s shape function helps us know the dimension of the dataframe. Here we have 20 features(columns) and 29165 observations(rows) for the training dataset.

cc_train_original.shape

(29165, 20)

And 20 features(columns) and 7292 observations(rows) for the testing dataset.

cc_test_original.shape

(7292, 20)

Finally, we will export the data as a CSV file on our local machine and create a copy of the dataset. Please note that these steps are optional. It is best practice to keep the original dataset untouched as a backup and work with the copy.

cc_train_original.to_csv('dataset/train.csv',index=False)

cc_test_original.to_csv('dataset/test.csv',index=False)

# creating a copy of the dataset so that the original stays untouched

cc_train_copy = cc_train_original.copy()

cc_test_copy = cc_test_original.copy()

Data at a glance

Now that we have split the dataset into training and testing datasets, we will focus on the training dataset for now and use the test dataset toward the end of this post.

Let’s review the first 5 rows again with the head() function.

cc_data_full_data.head()

| ID | Gender | Has a car | Has a property | Children count | Income | Employment status | Education level | Marital status | Dwelling | Age | Employment length | Has a mobile phone | Has a work phone | Has a phone | Has an email | Job title | Family member count | Account age | Is high risk | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 5008804 | M | Y | Y | 0 | 427500.0 | Working | Higher education | Civil marriage | Rented apartment | -12005 | -4542 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | NaN | 2.0 | -15.0 | 0 |

| 1 | 5008805 | M | Y | Y | 0 | 427500.0 | Working | Higher education | Civil marriage | Rented apartment | -12005 | -4542 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | NaN | 2.0 | -14.0 | 0 |

| 2 | 5008806 | M | Y | Y | 0 | 112500.0 | Working | Secondary / secondary special | Married | House / apartment | -21474 | -1134 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Security staff | 2.0 | -29.0 | 0 |

| 3 | 5008808 | F | N | Y | 0 | 270000.0 | Commercial associate | Secondary / secondary special | Single / not married | House / apartment | -19110 | -3051 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | Sales staff | 1.0 | -4.0 | 0 |

| 4 | 5008809 | F | N | Y | 0 | 270000.0 | Commercial associate | Secondary / secondary special | Single / not married | House / apartment | -19110 | -3051 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | Sales staff | 1.0 | -26.0 | 0 |

Now let’s see the data types of each of the features with the info() function.

cc_data_full_data.info()

<class 'pandas.core.frame.DataFrame'>

Int64Index: 36457 entries, 0 to 36456

Data columns (total 20 columns):

# Column Non-Null Count Dtype

--- ------ -------------- -----

0 ID 36457 non-null int64

1 Gender 36457 non-null object

2 Has a car 36457 non-null object

3 Has a property 36457 non-null object

4 Children count 36457 non-null int64

5 Income 36457 non-null float64

6 Employment status 36457 non-null object

7 Education level 36457 non-null object

8 Marital status 36457 non-null object

9 Dwelling 36457 non-null object

10 Age 36457 non-null int64

11 Employment length 36457 non-null int64

12 Has a mobile phone 36457 non-null int64

13 Has a work phone 36457 non-null int64

14 Has a phone 36457 non-null int64

15 Has an email 36457 non-null int64

16 Job title 25134 non-null object

17 Family member count 36457 non-null float64

18 Account age 36457 non-null float64

19 Is high risk 36457 non-null object

dtypes: float64(3), int64(8), object(9)

memory usage: 5.8+ MB

Let’s digest the information above. The first column is the indexes of the features; the second is the names; the third is the count of non-null values(only the job title has missing values); and the fourth is datatypes (objects which mean strings datatype, float or integer).

The describe() function gives us statistics about the numerical features in the dataset. These statistics include each numerical feature’s count, mean, standard deviation, interquartile range(25%, 50%, 75%), and minimum and maximum values.

cc_data_full_data.describe()

| ID | Children count | Income | Age | Employment length | Has a mobile phone | Has a work phone | Has a phone | Has an email | Family member count | Account age | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| count | 3.645700e+04 | 36457.000000 | 3.645700e+04 | 36457.000000 | 36457.000000 | 36457.0 | 36457.000000 | 36457.000000 | 36457.000000 | 36457.000000 | 36457.000000 |

| mean | 5.078227e+06 | 0.430315 | 1.866857e+05 | -15975.173382 | 59262.935568 | 1.0 | 0.225526 | 0.294813 | 0.089722 | 2.198453 | -26.164193 |

| std | 4.187524e+04 | 0.742367 | 1.017892e+05 | 4200.549944 | 137651.334859 | 0.0 | 0.417934 | 0.455965 | 0.285787 | 0.911686 | 16.501854 |

| min | 5.008804e+06 | 0.000000 | 2.700000e+04 | -25152.000000 | -15713.000000 | 1.0 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 1.000000 | -60.000000 |

| 25% | 5.042028e+06 | 0.000000 | 1.215000e+05 | -19438.000000 | -3153.000000 | 1.0 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 2.000000 | -39.000000 |

| 50% | 5.074614e+06 | 0.000000 | 1.575000e+05 | -15563.000000 | -1552.000000 | 1.0 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 2.000000 | -24.000000 |

| 75% | 5.115396e+06 | 1.000000 | 2.250000e+05 | -12462.000000 | -408.000000 | 1.0 | 0.000000 | 1.000000 | 0.000000 | 3.000000 | -12.000000 |

| max | 5.150487e+06 | 19.000000 | 1.575000e+06 | -7489.000000 | 365243.000000 | 1.0 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | 20.000000 | 0.000000 |

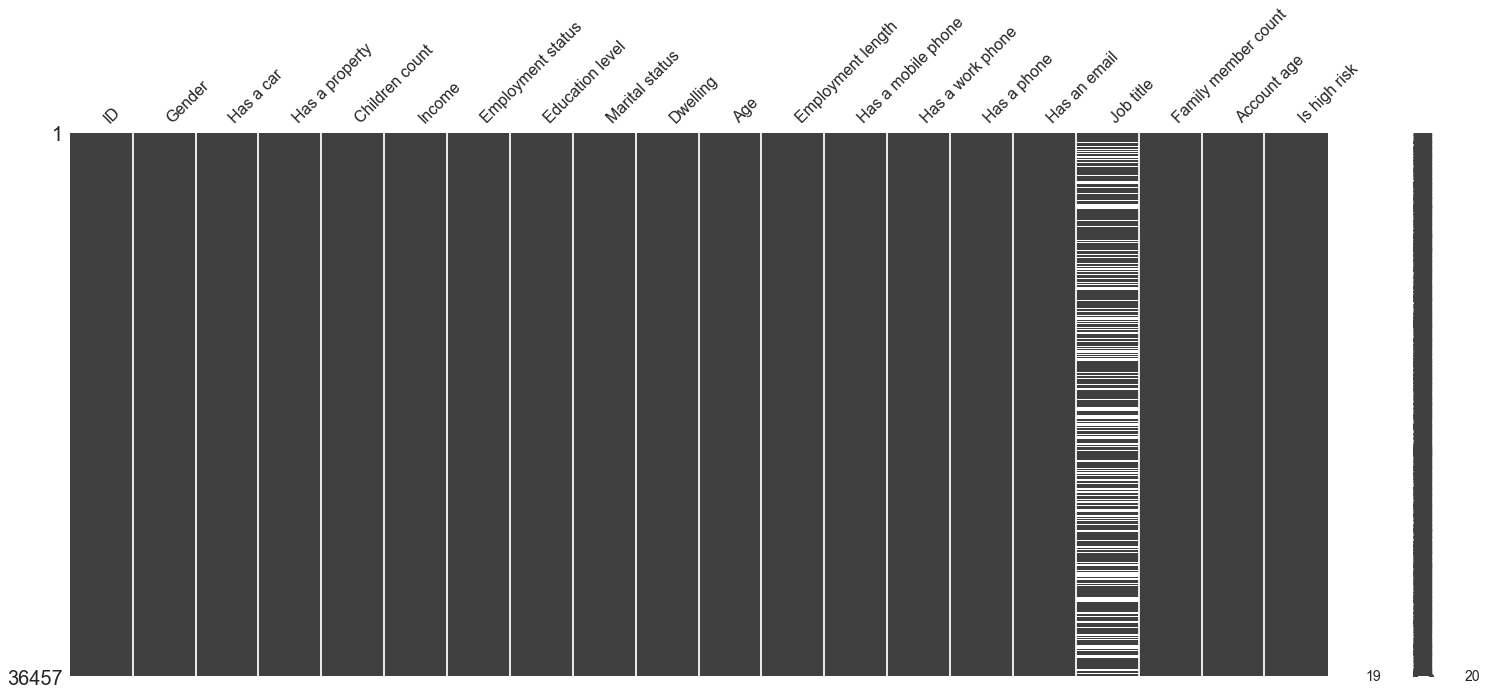

We will use the Missingno to visualize the missing values per feature using its matrix function.

msno.matrix(cc_data_full_data)

plt.show()

Here we can see that the Job title is the only feature with missing values. Slim white lines represent missing values.

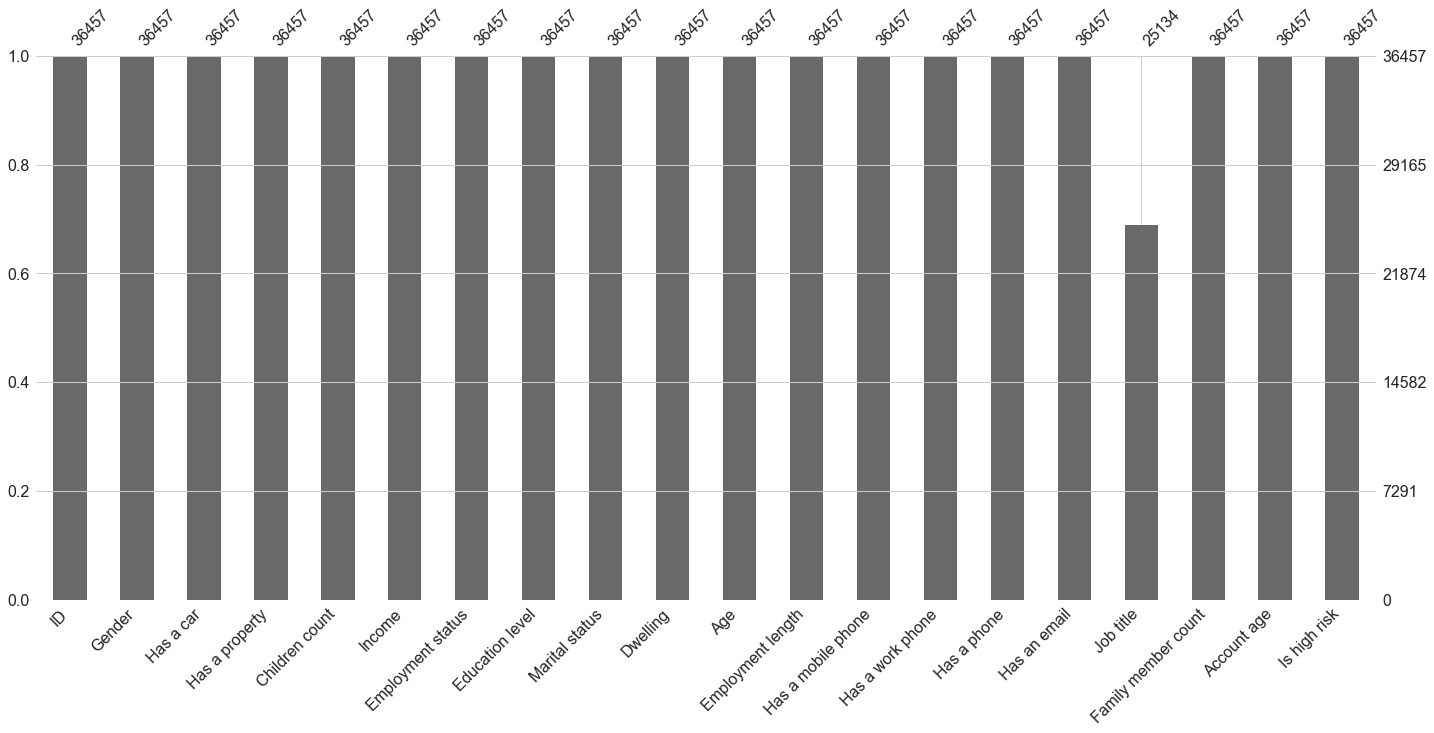

To see a clear representation of the missing values count, we can use its bar() function to have a barplot with the count of non-null values.

msno.bar(cc_data_full_data)

plt.show()

Now we will create functions to analyze each feature(Univariate analysis). Don’t worry too much about understanding these functions, as we will see how they are used during the exploratory data analysis section.

Our first function value_cnt_norm_cal is used to calculate the count of each class in a feature with its frequency (normalized on a scale of 100)

def value_cnt_norm_cal(df,feature):

'''Function that will return the value count and frequency of each observation within a feature'''

# get the value counts of each feature

ftr_value_cnt = df[feature].value_counts()

# normalize the value counts on a scale of 100

ftr_value_cnt_norm = df[feature].value_counts(normalize=True) * 100

# concatenate the value counts with normalized value count column wise

ftr_value_cnt_concat = pd.concat([ftr_value_cnt, ftr_value_cnt_norm], axis=1)

# give it a column name

ftr_value_cnt_concat.columns = ['Count', 'Frequency (%)']

# return the dataframe

return ftr_value_cnt_concat

gen_info_feat returned the description, the datatype, statistics, the value counts and frequencies

Note: I have used the if statement to handle features differently depending on their data type and characteristics. For example, I divided age by 365.25 and changed it to a positive value because it is expressed in days instead of years. Same as employment length; however, we did not print the value count for account age.

def gen_info_feat(df,feature):

'''function to display general information about the feature'''

# if the feature is Age

if feature == 'Age':

# change the feature to be expressed in positive numbers of days and divide by 365.25 to be expressed in years and get the description

print('Description:\n{}'.format((np.abs(df[feature])/365.25).describe()))

# print separators

print('*'*50)

# print the datatype

print('Object type:{}'.format(df[feature].dtype))

# if the feature is employment length

if feature == 'Employment length':

# select only the rows where the rows are negative values to ignore those who have retired or are unemployed

employment_len_no_ret = cc_train_copy['Employment length'][cc_train_copy['Employment length'] < 0]

# change the negative values to positive values

employment_len_no_ret_yrs = np.abs(employment_len_no_ret)/365.25

# print the descriptions

print('Description:\n{}'.format((employment_len_no_ret_yrs).describe()))

# print separators

print('*'*50)

# print the datatype

print('Object type:{}'.format(employment_len_no_ret.dtype))

# if the feature is account age

if feature == 'Account age' or feature == 'Income':

# change the account age to a positive number of months and get the description

print('Description:\n{}'.format((np.abs(df[feature])).describe()))

# print separators

print('*'*50)

# print the datatype

print('Object type:{}'.format(df[feature].dtype))

# if it is any other feature

else:

# get the description

print('Description:\n{}'.format(df[feature].describe()))

# print separators

print('*'*50)

# print the datatype

print('Object type:\n{}'.format(df[feature].dtype))

# print separators

print('*'*50)

# calling the value_cnt_norm_cal function previously seen

value_cnt = value_cnt_norm_cal(df,feature)

# print the result

print('Value count:\n{}'.format(value_cnt))

The following function prints a pie chart.

def create_pie_plot(df,feature):

'''function to create a pie chart plot'''

# if the feature is dwelling or education level

if feature == 'Dwelling' or feature == 'Education level':

# calling the value_cnt_norm_cal function previously seen

ratio_size = value_cnt_norm_cal(df, feature)

# get how many classes we have

ratio_size_len = len(ratio_size.index)

ratio_list = []

# loop till the max range

for i in range(ratio_size_len):

#append the ratio of each feature to the list

ratio_list.append(ratio_size.iloc[i]['Frequency (%)'])

# create a subplot

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(8,8))

# %1.2f%% display decimals in the pie chart with 2 decimal places

plt.pie(ratio_list, startangle=90, wedgeprops={'edgecolor' :'black'})

# add a title to the chart

plt.title('Pie chart of {}'.format(feature))

# add a legend to the chart

plt.legend(loc='best',labels=ratio_size.index)

# center the plot in the subplot

plt.axis('equal')

# return the plot

return plt.show()

# for other features

else:

ratio_size = value_cnt_norm_cal(df, feature)

ratio_size_len = len(ratio_size.index)

ratio_list = []

for i in range(ratio_size_len):

ratio_list.append(ratio_size.iloc[i]['Frequency (%)'])

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(8,8))

# %1.2f%% display decimals in the pie chart with 2 decimal places

plt.pie(ratio_list, labels=ratio_size.index, autopct='%1.2f%%', startangle=90, wedgeprops={'edgecolor' :'black'})

plt.title('Pie chart of {}'.format(feature))

plt.legend(loc='best')

plt.axis('equal')

return plt.show()

The next function create a bar plot.

def create_bar_plot(df,feature):

'''function to create a bar chart plot'''

if feature == 'Marital status' or feature == 'Dwelling' or feature == 'Job title' or feature == 'Employment status' or feature == 'Education level':

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(6,10))

# create a barplot using seaborn with X-axis the indexes from value_cnt_norm_cal function and Y axis we use the value counts from the same function

sns.barplot(x=value_cnt_norm_cal(df,feature).index,y=value_cnt_norm_cal(df,feature).values[:,0])

# set the plot's tick labels to the index from the value_cnt_norm_cal function, rotate those ticks by 45 degrees

ax.set_xticklabels(labels=value_cnt_norm_cal(df,feature).index,rotation=45,ha='right')

# Give the X-axis the same label as the feature name

plt.xlabel('{}'.format(feature))

# Give the Y-axis the label "Count"

plt.ylabel('Count')

# Give the plot a title

plt.title('{} count'.format(feature))

# Return the title

return plt.show()

else:

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(6,10))

sns.barplot(x=value_cnt_norm_cal(df,feature).index,y=value_cnt_norm_cal(df,feature).values[:,0])

plt.xlabel('{}'.format(feature))

plt.ylabel('Count')

plt.title('{} count'.format(feature))

return plt.show()

This function will create a box plot for continuous variables.

Note: Depending on which transformation needs to be done on each feature, we have used a switch statement to handle the different feature that requires different handling.

def create_box_plot(df,feature):

'''function to create a box plot'''

if feature == 'Age':

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(2,8))

# change the feature to be expressed in positive numbers days

sns.boxplot(y=np.abs(df[feature])/365.25)

plt.title('{} distribution(Boxplot)'.format(feature))

return plt.show()

if feature == 'Children count':

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(2,8))

sns.boxplot(y=df[feature])

plt.title('{} distribution(Boxplot)'.format(feature))

# use the numpy arrange to populate the Y ticks starting from 0 till the max count of children with an interval of 1 as follows np.arange(start, stop, step)

plt.yticks(np.arange(0,df[feature].max(),1))

return plt.show()

if feature == 'Employment length':

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(2,8))

employment_len_no_ret = cc_train_copy['Employment length'][cc_train_copy['Employment length'] < 0]

# employment length in days is a negative number, so we need to change it to positive and change it to years

employment_len_no_ret_yrs = np.abs(employment_len_no_ret)/365.25

# create a boxplot with seaborn

sns.boxplot(y=employment_len_no_ret_yrs)

plt.title('{} distribution(Boxplot)'.format(feature))

plt.yticks(np.arange(0,employment_len_no_ret_yrs.max(),2))

return plt.show()

if feature == 'Income':

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(2,8))

sns.boxplot(y=df[feature])

plt.title('{} distribution(Boxplot)'.format(feature))

# suppress the scientific notation

ax.get_yaxis().set_major_formatter(

matplotlib.ticker.FuncFormatter(lambda x, p: format(int(x), ',')))

return plt.show()

if feature == 'Account age':

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(2,8))

sns.boxplot(y=np.abs(df[feature]))

plt.title('{} distribution(Boxplot)'.format(feature))

return plt.show()

else:

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(2,8))

sns.boxplot(y=df[feature])

plt.title('{} distribution(Boxplot)'.format(feature))

return plt.show()

This function will plot a histogram.

def create_hist_plot(df,feature, the_bins=50):

'''function to create a histogram plot'''

if feature == 'Age':

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(18,10))

# change the feature to be expressed in positive numbers days

sns.histplot(np.abs(df[feature])/365.25,bins=the_bins,kde=True)

plt.title('{} distribution'.format(feature))

return plt.show()

if feature == 'Income':

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(18,10))

sns.histplot(df[feature],bins=the_bins,kde=True)

# suppress scientific notation

ax.get_xaxis().set_major_formatter(

matplotlib.ticker.FuncFormatter(lambda x, p: format(int(x), ',')))

plt.title('{} distribution'.format(feature))

return plt.show()

if feature == 'Employment length':

employment_len_no_ret = cc_train_copy['Employment length'][cc_train_copy['Employment length'] < 0]

# change the feature to be expressed in positive numbers days

employment_len_no_ret_yrs = np.abs(employment_len_no_ret)/365.25

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(18,10))

sns.histplot(employment_len_no_ret_yrs,bins=the_bins,kde=True)

plt.title('{} distribution'.format(feature))

return plt.show()

if feature == 'Account age':

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(18,10))

sns.histplot(np.abs(df[feature]),bins=the_bins,kde=True)

plt.title('{} distribution'.format(feature))

return plt.show()

else:

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(18,10))

sns.histplot(df[feature],bins=the_bins,kde=True)

plt.title('{} distribution'.format(feature))

return plt.show()

This function will plot two box plots, one is for low-risk (good client), and the other is for high-risk (bad client) applicants. On the Y axis, we have the continuous features we are studying. Again don’t worry too much, as we will see these functions in action in the sections below.

def low_high_risk_box_plot(df,feature):

'''High risk vs low risk applicants compared on a box plot'''

if feature == 'Age':

print(np.abs(df.groupby('Is high risk')[feature].mean()/365.25))

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(5,8))

# Place on the Y-axis age and X-axis the two box plot (is high risk: No and Yes)

sns.boxplot(y=np.abs(df[feature])/365.25,x=df['Is high risk'])

# add ticks to the X axis

plt.xticks(ticks=[0,1],labels=['no','yes'])

plt.title('High risk individuals grouped by age')

return plt.show()

if feature == 'Income':

print(np.abs(df.groupby('Is high risk')[feature].mean()))

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(5,8))

sns.boxplot(y=np.abs(df[feature]),x=df['Is high risk'])

plt.xticks(ticks=[0,1],labels=['no','yes'])

# suppress the scientific notation

ax.get_yaxis().set_major_formatter(

matplotlib.ticker.FuncFormatter(lambda x, p: format(int(x), ',')))

plt.title('High risk individuals grouped by {}'.format(feature))

return plt.show()

if feature == 'Employment length':

# checking is an applicant is high risk or not (for those who have negative employment length mean only those who are employed)

employment_no_ret = cc_train_copy['Employment length'][cc_train_copy['Employment length'] <0]

employment_no_ret_idx = employment_no_ret.index

employment_len_no_ret_yrs = np.abs(employment_no_ret)/365.25

# extract those who are employed from the original dataframe and return only the employment length and Is high risk columns

employment_no_ret_df = cc_train_copy.iloc[employment_no_ret_idx][['Employment length','Is high risk']]

# return the mean employment length group by how risky is the applicant

employment_no_ret_is_high_risk = employment_no_ret_df.groupby('Is high risk')['Employment length'].mean()

print(np.abs(employment_no_ret_is_high_risk)/365.25)

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(5,8))

sns.boxplot(y=employment_len_no_ret_yrs,x=df['Is high risk'])

plt.xticks(ticks=[0,1],labels=['no','yes'])

plt.title('High vs low risk individuals grouped by {}'.format(feature))

return plt.show()

else:

print(np.abs(df.groupby('Is high risk')[feature].mean()))

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(5,8))

sns.boxplot(y=np.abs(df[feature]),x=df['Is high risk'])

plt.xticks(ticks=[0,1],labels=['no','yes'])

plt.title('High risk individuals grouped by {}'.format(feature))

return plt.show()

This function is similar to the previous one; the only difference is that it uses a bar plot which is a count of classes for comparison purposes between high risk and low risk.

def low_high_risk_bar_plot(df,feature):

'''High risk vs low risk applicants compared on a bar plot'''

# get the sum of high-risk clients grouped by a specific feature

is_high_risk_grp = df.groupby(feature)['Is high risk'].sum()

# sort is a descending order

is_high_risk_grp_srt = is_high_risk_grp.sort_values(ascending=False)

print(dict(is_high_risk_grp_srt))

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(6,10))

# plot on the X axis the indexes which correspond to classes, and on the Y axis, the count

sns.barplot(x=is_high_risk_grp_srt.index,y=is_high_risk_grp_srt.values)

# add the labels to the plot

ax.set_xticklabels(labels=is_high_risk_grp_srt.index,rotation=45, ha='right')

plt.ylabel('Count')

plt.title('High risk applicants count grouped by {}'.format(feature))

return plt.show()

Now let’s properly start our exploratory data analysis with a univariate analysis. Univariate analysis is an analysis of each feature individually in the dataset.

Univariate analysis

Gender

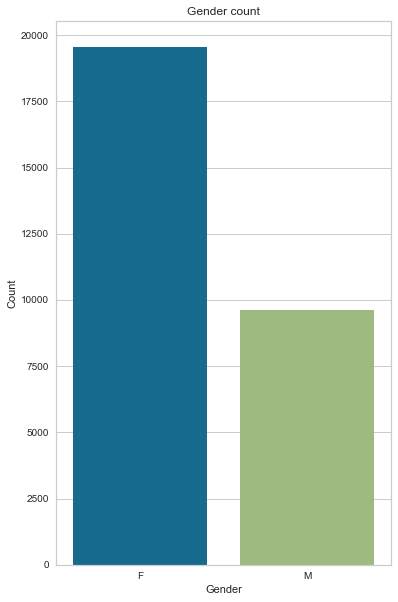

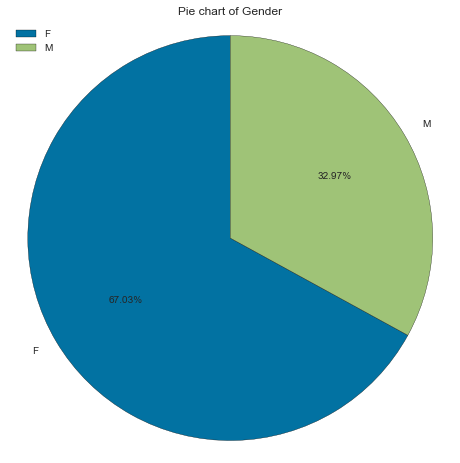

We start with Gender. We call gen_info_feat and see that we have two unique classes F (for female) and M (for male), with 19549 and 9616 occurrences, respectively. Percentage-wise we have 67.02% females and 32.97% males.

gen_info_feat(cc_train_copy,'Gender')

Description:

count 29165

unique 2

top F

freq 19549

Name: Gender, dtype: object

**************************************************

Object type:

object

**************************************************

Value count:

Count Frequency (%)

F 19549 67.028973

M 9616 32.971027

create_bar_plot(cc_train_copy,'Gender')

create_pie_plot(cc_train_copy,'Gender')

Age

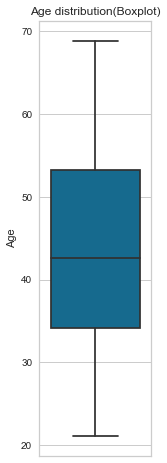

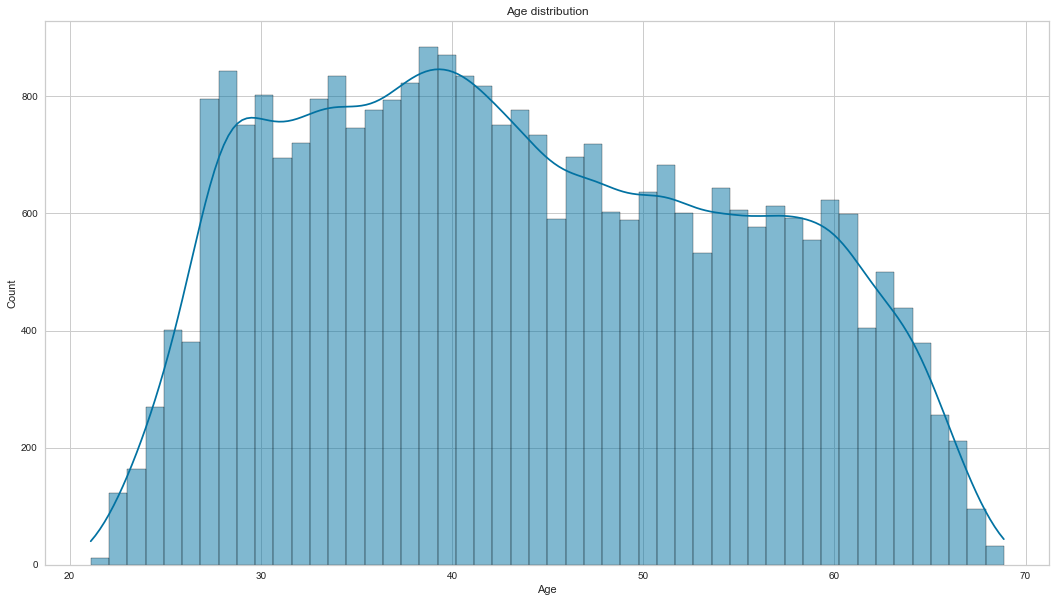

Now let’s look at Age; since age is a continuous variable, we will process it differently than Gender. Using the gen_info_feat function, we look at the mean, standard deviation, minimum, maximum and interquartile range. Then we plot that information on a box plot by calling the create_box_plot function. With that, we can see that the youngest applicant(s) is 21 years old while the oldest is 68. With an average of 43.7 and a median of 42.6 (outliers insensitive)

gen_info_feat(cc_train_copy,'Age')

Description:

count 29165.000000

mean 43.749425

std 11.507180

min 21.095140

25% 34.154689

50% 42.614648

75% 53.234771

max 68.862423

Name: Age, dtype: float64

**************************************************

Object type:int64

Description:

count 29165.000000

mean -15979.477490

std 4202.997485

min -25152.000000

25% -19444.000000

50% -15565.000000

75% -12475.000000

max -7705.000000

Name: Age, dtype: float64

**************************************************

Object type:

int64

**************************************************

Value count:

Count Frequency (%)

-12676 44 0.150866

-15519 44 0.150866

-16896 33 0.113149

-16053 26 0.089148

-16768 26 0.089148

... ... ...

-18253 1 0.003429

-23429 1 0.003429

-15478 1 0.003429

-21648 1 0.003429

-19564 1 0.003429

[6794 rows x 2 columns]

create_box_plot(cc_train_copy,'Age')

After that, we plot its histogram with the kernel density estimator. ``` Age `` is not normally distributed; it is slightly positively skewed.

create_hist_plot(cc_train_copy,'Age')

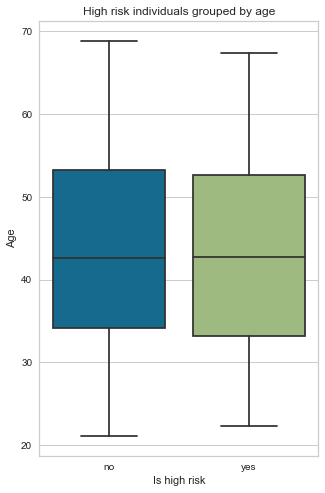

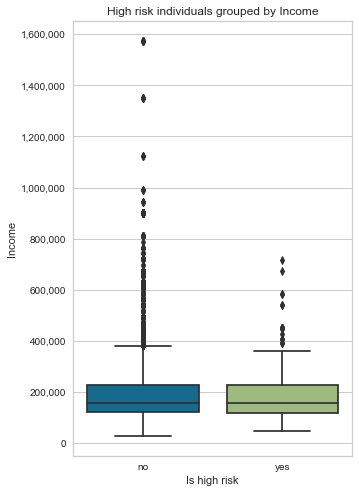

Now we perform a quick bivariate analysis (comparison of two features) of Age and the target variable Is high risk. The blue box plot represents a good client (is high risk = No), and the green box plot represents a bad client (is high risk = Yes). We can see no significant difference between the age of those who are high risk and those who are not. The mean age for both groups is around 43 years old, and there is no correlation between the age and risk factors of the applicant.

low_high_risk_box_plot(cc_train_copy,'Age')

Is high risk

0 43.753103

1 43.538148

Name: Age, dtype: float64

Marital status

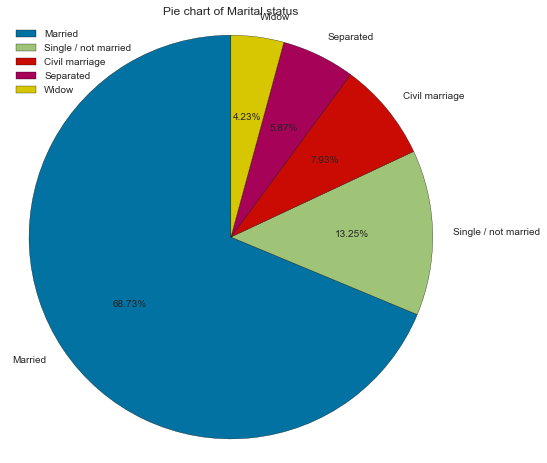

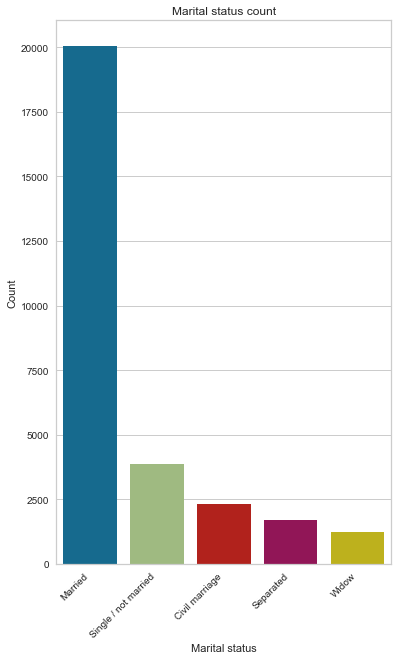

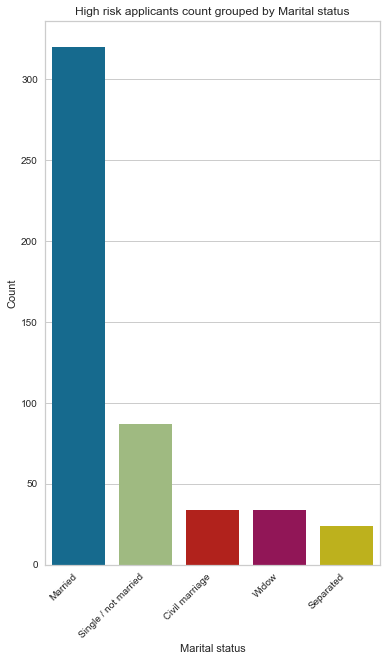

There are 5 unique classes for this feature. Married constitutes the most significant proportion of marital status, with 68% far ahead of single, as seen on the pie chart and bar charts. Another interesting observation is that even though we have a higher number of applicants who are separated than widows, it seems that widow applicants are bad clients than those who are separated by a small margin.

gen_info_feat(cc_train_copy,'Marital status')

Description:

count 29165

unique 5

top Married

freq 20044

Name: Marital status, dtype: object

**************************************************

Object type:

object

**************************************************

Value count:

Count Frequency (%)

Married 20044 68.726213

Single / not married 3864 13.248757

Civil marriage 2312 7.927310

Separated 1712 5.870050

Widow 1233 4.227670

create_pie_plot(cc_train_copy,'Marital status')

create_bar_plot(cc_train_copy,'Marital status')

low_high_risk_bar_plot(cc_train_copy,'Marital status')

{'Married': 320, 'Single / not married': 87, 'Civil marriage': 34, 'Widow': 34, 'Separated': 24}

Family member count

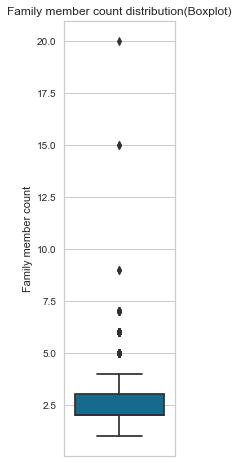

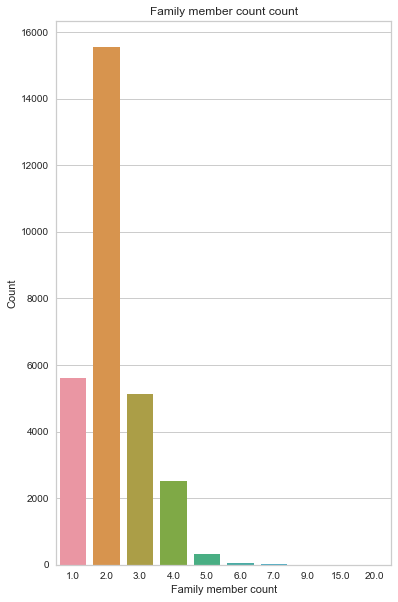

Family member count is a numerical feature, with the median of 2 family members representing 53% (count = 15552) of all the counts, followed by a single family member with 19% (count = 5613). Looking at the box plot, we have 6 outliers; 2 are extreme, with 20 and 15 members in their household.

gen_info_feat(cc_train_copy,'Family member count')

Description:

count 29165.000000

mean 2.197531

std 0.912189

min 1.000000

25% 2.000000

50% 2.000000

75% 3.000000

max 20.000000

Name: Family member count, dtype: float64

**************************************************

Object type:

float64

**************************************************

Value count:

Count Frequency (%)

2.0 15552 53.324190

1.0 5613 19.245671

3.0 5121 17.558718

4.0 2503 8.582205

5.0 309 1.059489

6.0 48 0.164581

7.0 14 0.048003

9.0 2 0.006858

15.0 2 0.006858

20.0 1 0.003429

create_box_plot(cc_train_copy,'Family member count')

create_bar_plot(cc_train_copy,'Family member count')

Children count

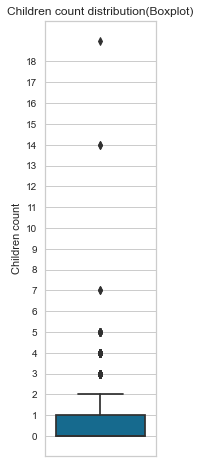

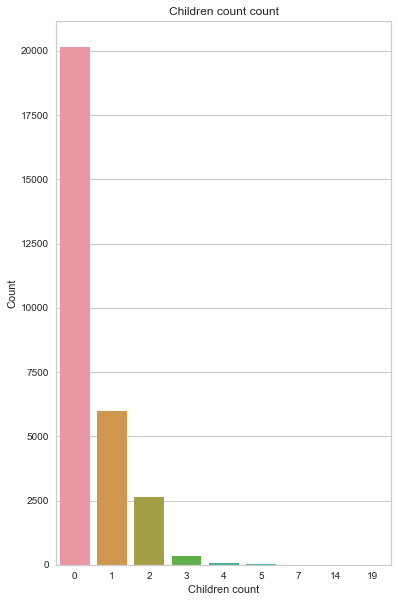

From the chart below, we can see that most applicants don’t have any children. Again, we have 6 outliers, most probably the same seen from the family member count.

gen_info_feat(cc_train_copy,'Children count')

Description:

count 29165.000000

mean 0.430790

std 0.741882

min 0.000000

25% 0.000000

50% 0.000000

75% 1.000000

max 19.000000

Name: Children count, dtype: float64

**************************************************

Object type:

int64

**************************************************

Value count:

Count Frequency (%)

0 20143 69.065661

1 6003 20.582890

2 2624 8.997086

3 323 1.107492

4 52 0.178296

5 15 0.051432

7 2 0.006858

14 2 0.006858

19 1 0.003429

create_box_plot(cc_train_copy,'Children count')

create_bar_plot(cc_train_copy,'Children count')

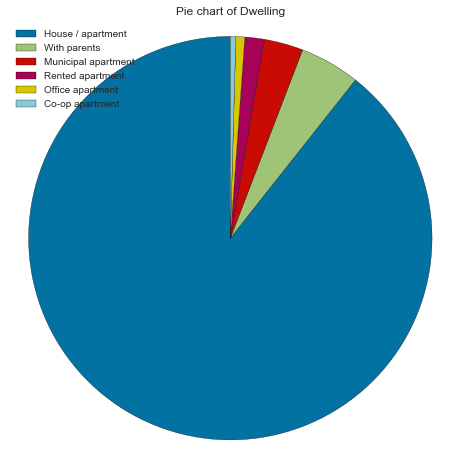

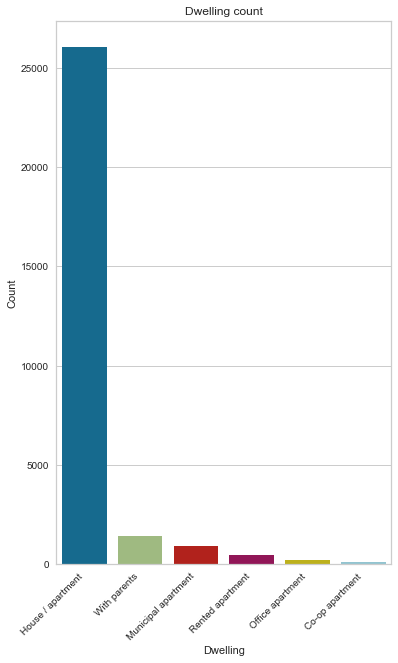

Dwelling type

89% of applicants live in houses/apartments by a substantial margin.

gen_info_feat(cc_train_copy,'Dwelling')

Description:

count 29165

unique 6

top House / apartment

freq 26059

Name: Dwelling, dtype: object

**************************************************

Object type:

object

**************************************************

Value count:

Count Frequency (%)

House / apartment 26059 89.350249

With parents 1406 4.820847

Municipal apartment 912 3.127036

Rented apartment 453 1.553232

Office apartment 208 0.713184

Co-op apartment 127 0.435453

create_pie_plot(cc_train_copy,'Dwelling')

create_bar_plot(cc_train_copy,'Dwelling')

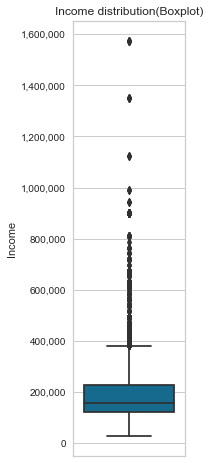

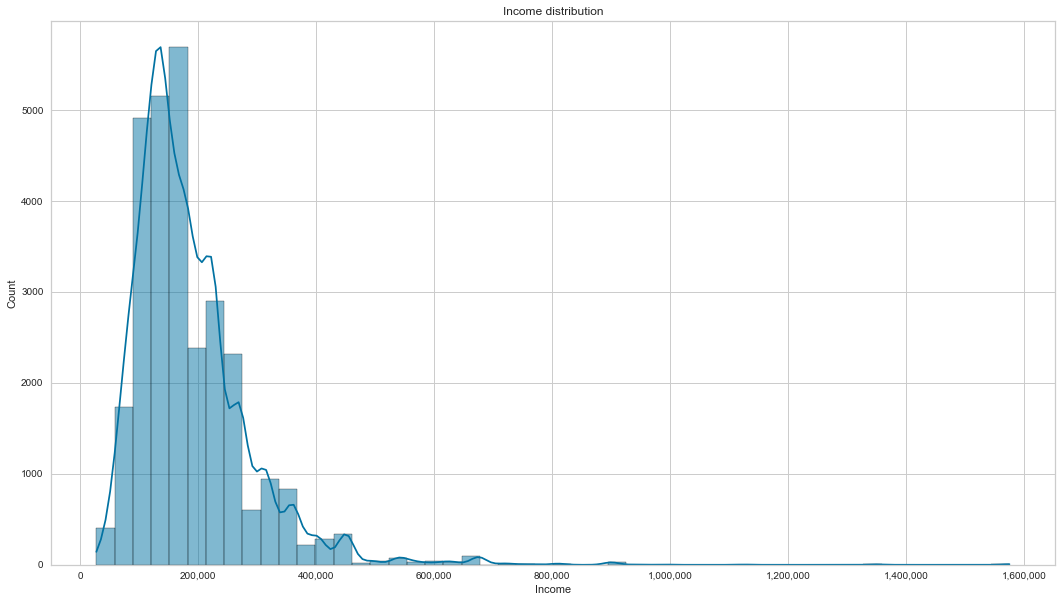

Income

Looking at the results from the gen_info_feat function, we can see that the average mean income is 186890, but this amount factors in outliers. Most people make 157500 (median income) if we ignore the outliers. We have 3 applicants who make more than 1000000.

This feature is also positively skewed. Focusing on the income box plot of good and bad clients, they all have roughly similar incomes.

pd.set_option('display.float_format', lambda x: '%.2f' % x)

gen_info_feat(cc_train_copy,'Income')

Description:

count 29165.00

mean 186890.39

std 101409.64

min 27000.00

25% 121500.00

50% 157500.00

75% 225000.00

max 1575000.00

Name: Income, dtype: float64

**************************************************

Object type:float64

create_box_plot(cc_train_copy,'Income')

create_hist_plot(cc_train_copy,'Income')

- bivariate analysis with target variable

low_high_risk_box_plot(cc_train_copy,'Income')

Is high risk

0 186913.94

1 185537.26

Name: Income, dtype: float64

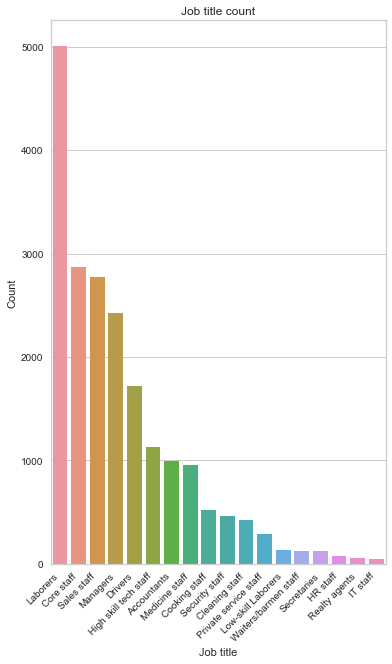

Job title

The most common Job title is laborers by a large margin (24.85%), followed by core staff (14.23%), sales staff (13.77%) and managers (12.03%). We also have 30.95% of missing data.

gen_info_feat(cc_train_copy,'Job title')

Description:

count 20138

unique 18

top Laborers

freq 5004

Name: Job title, dtype: object

**************************************************

Object type:

object

**************************************************

Value count:

Count Frequency (%)

Laborers 5004 24.85

Core staff 2866 14.23

Sales staff 2773 13.77

Managers 2422 12.03

Drivers 1722 8.55

High skill tech staff 1133 5.63

Accountants 998 4.96

Medicine staff 956 4.75

Cooking staff 521 2.59

Security staff 464 2.30

Cleaning staff 425 2.11

Private service staff 287 1.43

Low-skill Laborers 138 0.69

Waiters/barmen staff 127 0.63

Secretaries 122 0.61

HR staff 72 0.36

Realty agents 60 0.30

IT staff 48 0.24

job_title_nan_count = cc_train_copy['Job title'].isna().sum()

job_title_nan_count

9027

rows_total_count = cc_train_copy.shape[0]

print('The percentage of missing rows is {:.2f} %'.format(job_title_nan_count * 100 / rows_total_count))

The percentage of missing rows is 30.95 %

create_bar_plot(cc_train_copy,'Job title')

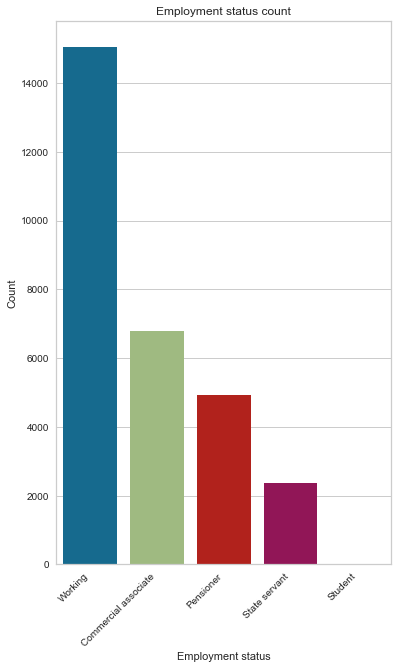

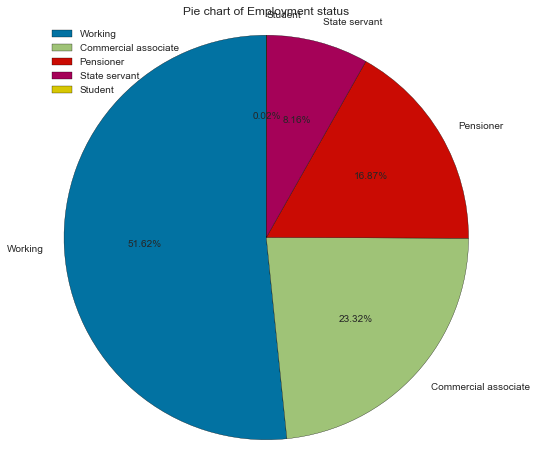

Employment status

Most applicants are working (51.62%); the next most represented status is commercial associate, followed by the pensioner.

gen_info_feat(cc_train_copy,'Employment status')

Description:

count 29165

unique 5

top Working

freq 15056

Name: Employment status, dtype: object

**************************************************

Object type:

object

**************************************************

Value count:

Count Frequency (%)

Working 15056 51.62

Commercial associate 6801 23.32

Pensioner 4920 16.87

State servant 2381 8.16

Student 7 0.02

create_bar_plot(cc_train_copy,'Employment status')

create_pie_plot(cc_train_copy,'Employment status')

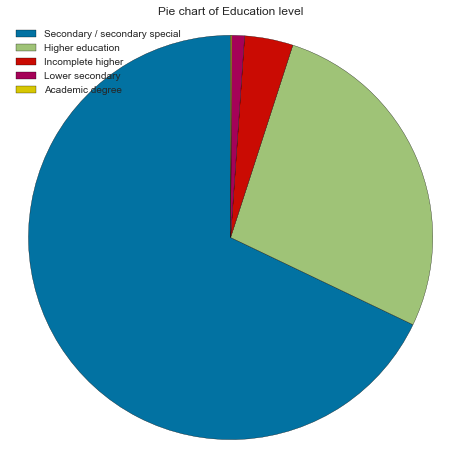

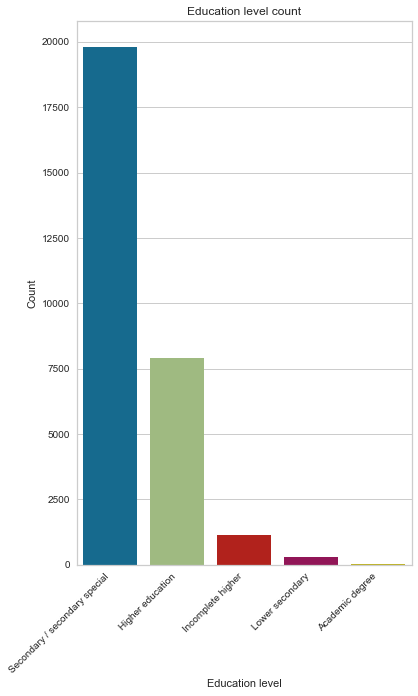

Education level

Most applicants have completed their secondary degree (67.90%) ¼ completed their higher education.

gen_info_feat(cc_train_copy,'Education level')

Description:

count 29165

unique 5

top Secondary / secondary special

freq 19803

Name: Education level, dtype: object

**************************************************

Object type:

object

**************************************************

Value count:

Count Frequency (%)

Secondary / secondary special 19803 67.90

Higher education 7910 27.12

Incomplete higher 1129 3.87

Lower secondary 298 1.02

Academic degree 25 0.09

create_pie_plot(cc_train_copy,'Education level')

create_bar_plot(cc_train_copy,'Education level')

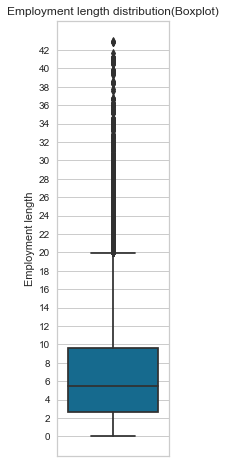

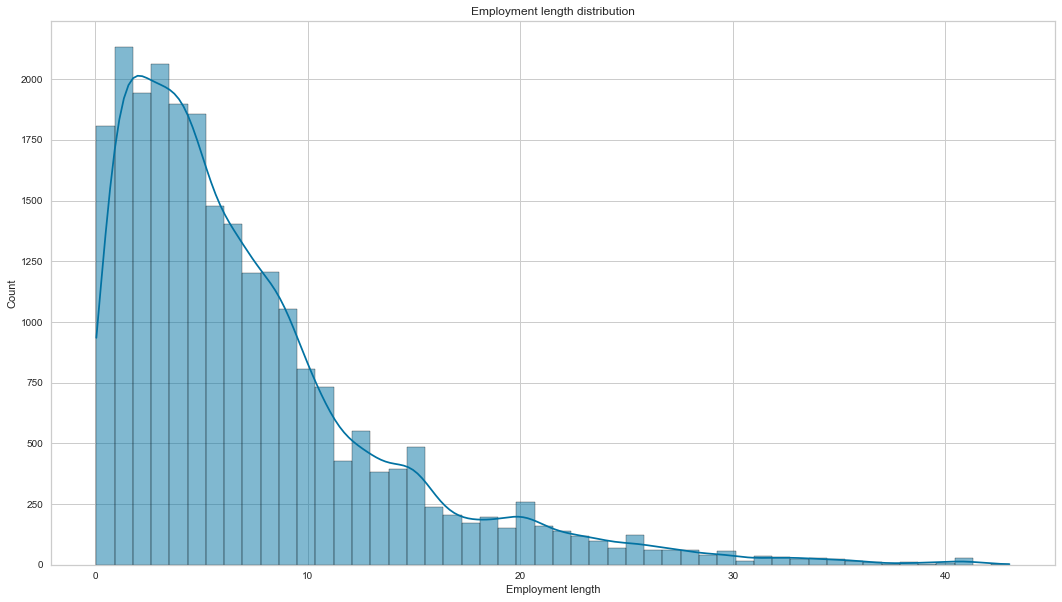

Employment length

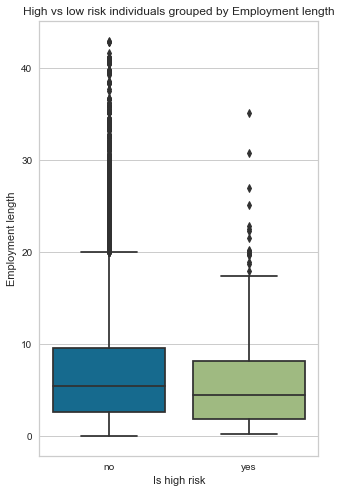

Most applicants have been working between 5 to 7 years on average, and we also have many outliers who have been working for more than 20 years+. The employment length histogram is positively skewed. Finally, bad clients have a low employment length of 5 versus 7 years for good clients.

gen_info_feat(cc_train_copy,'Employment length')

Description:

count 24257.00

mean 7.26

std 6.46

min 0.05

25% 2.68

50% 5.45

75% 9.60

max 43.02

Name: Employment length, dtype: float64

**************************************************

Object type:int64

Description:

count 29165.00

mean 59257.76

std 137655.88

min -15713.00

25% -3153.00

50% -1557.00

75% -412.00

max 365243.00

Name: Employment length, dtype: float64

**************************************************

Object type:

int64

**************************************************

Value count:

Count Frequency (%)

365243 4908 16.83

-401 61 0.21

-200 55 0.19

-2087 53 0.18

-1539 51 0.17

... ... ...

-8369 1 0.00

-6288 1 0.00

-6303 1 0.00

-3065 1 0.00

-8256 1 0.00

[3483 rows x 2 columns]

create_box_plot(cc_train_copy,'Employment length')

create_hist_plot(cc_train_copy,'Employment length')

- bivariate analysis with target variable

# distribution of employment length for good vs bad client

# Here 0 means No and 1 means Yes

low_high_risk_box_plot(cc_train_copy,'Employment length')

Is high risk

0 7.29

1 5.75

Name: Employment length, dtype: float64

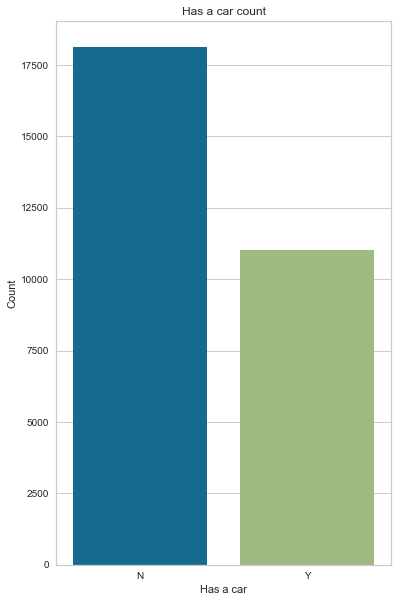

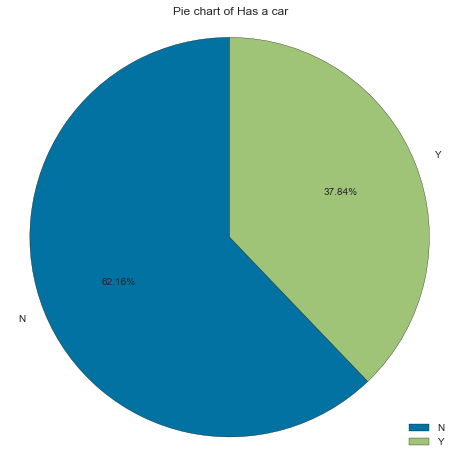

Has a car

Most applicants don’t own a car (62% of applicants).

gen_info_feat(cc_train_copy,'Has a car')

Description:

count 29165

unique 2

top N

freq 18128

Name: Has a car, dtype: object

**************************************************

Object type:

object

**************************************************

Value count:

Count Frequency (%)

N 18128 62.16

Y 11037 37.84

create_bar_plot(cc_train_copy,'Has a car')

create_pie_plot(cc_train_copy,'Has a car')

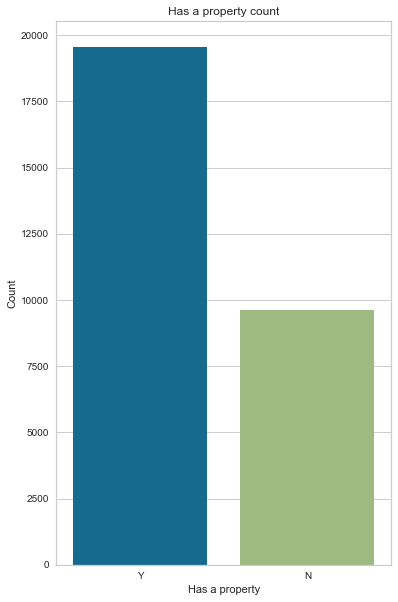

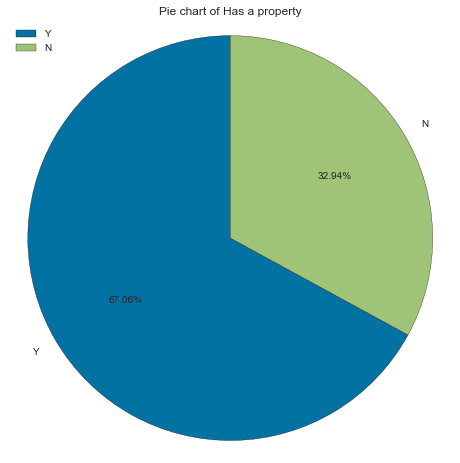

Has a property

Most applicants own a property (67% of applicants)

gen_info_feat(cc_train_copy,'Has a property')

Description:

count 29165

unique 2

top Y

freq 19557

Name: Has a property, dtype: object

**************************************************

Object type:

object

**************************************************

Value count:

Count Frequency (%)

Y 19557 67.06

N 9608 32.94

create_bar_plot(cc_train_copy,'Has a property')

create_pie_plot(cc_train_copy,'Has a property')

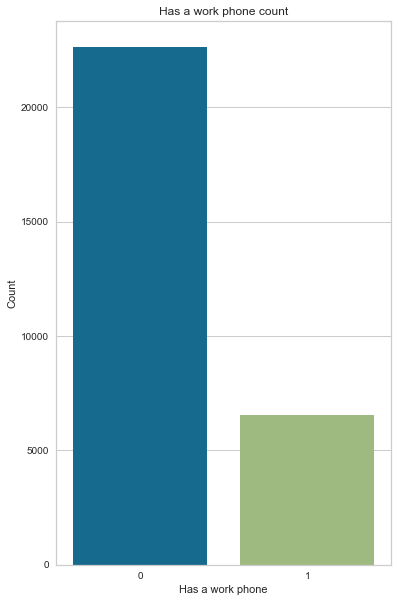

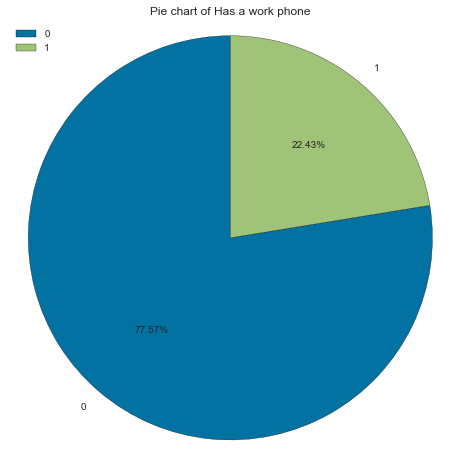

Has a work phone

More than ¾ of applicants don’t have a work phone

Note: Here, 0 represent no and 1 represents yes

gen_info_feat(cc_train_copy,'Has a work phone')

Description:

count 29165.00

mean 0.22

std 0.42

min 0.00

25% 0.00

50% 0.00

75% 0.00

max 1.00

Name: Has a work phone, dtype: float64

**************************************************

Object type:

int64

**************************************************

Value count:

Count Frequency (%)

0 22623 77.57

1 6542 22.43

create_bar_plot(cc_train_copy,'Has a work phone')

create_pie_plot(cc_train_copy,'Has a work phone')

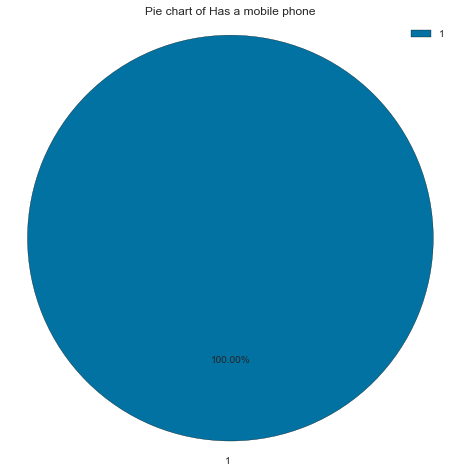

Has a mobile phone

All the applicants, without exception, have a mobile phone.

Note: Here, 0 is no and 1 is yes

gen_info_feat(cc_train_copy,'Has a mobile phone')

Description:

count 29165.00

mean 1.00

std 0.00

min 1.00

25% 1.00

50% 1.00

75% 1.00

max 1.00

Name: Has a mobile phone, dtype: float64

**************************************************

Object type:

int64

**************************************************

Value count:

Count Frequency (%)

1 29165 100.00

create_pie_plot(cc_train_copy,'Has a mobile phone')

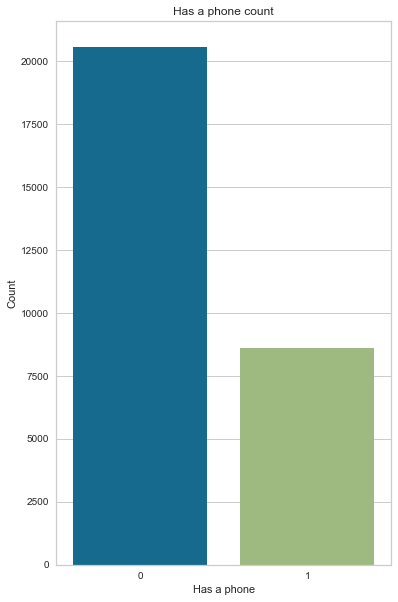

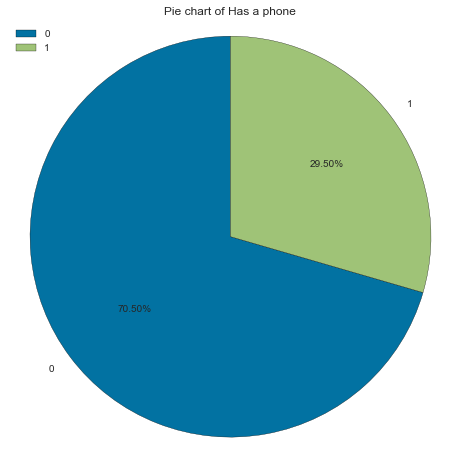

Has a phone

70% of applicants don’t have a phone (probably a home phone)

Note: Here, 0 is no and 1 is yes

gen_info_feat(cc_train_copy,'Has a phone')

Description:

count 29165.00

mean 0.29

std 0.46

min 0.00

25% 0.00

50% 0.00

75% 1.00

max 1.00

Name: Has a phone, dtype: float64

**************************************************

Object type:

int64

**************************************************

Value count:

Count Frequency (%)

0 20562 70.50

1 8603 29.50

create_bar_plot(cc_train_copy,'Has a phone')

create_pie_plot(cc_train_copy,'Has a phone')

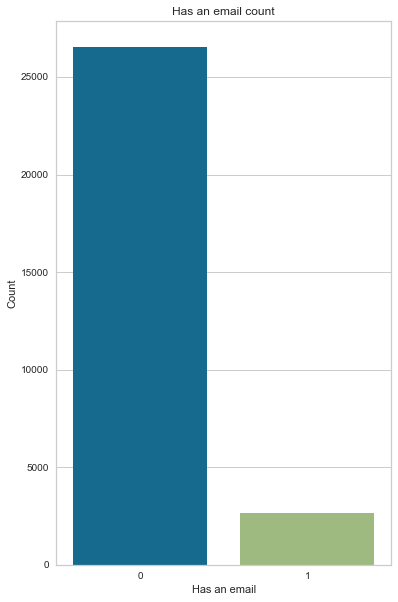

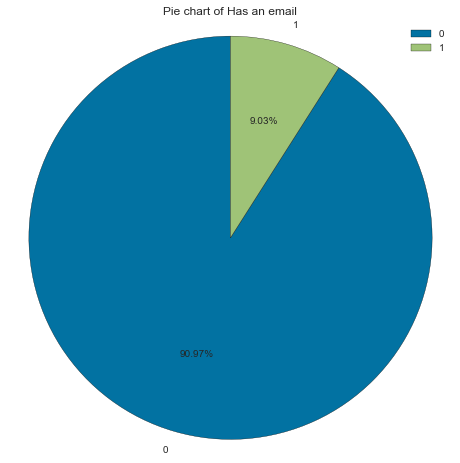

Has an email

Interestingly, more than 90 % of applicants don’t have an email

Note: Here, 0 is no and 1 is yes

gen_info_feat(cc_train_copy,'Has an email')

Description:

count 29165.00

mean 0.09

std 0.29

min 0.00

25% 0.00

50% 0.00

75% 0.00

max 1.00

Name: Has an email, dtype: float64

**************************************************

Object type:

int64

**************************************************

Value count:

Count Frequency (%)

0 26532 90.97

1 2633 9.03

create_bar_plot(cc_train_copy,'Has an email')

create_pie_plot(cc_train_copy,'Has an email')

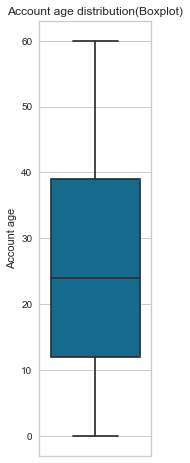

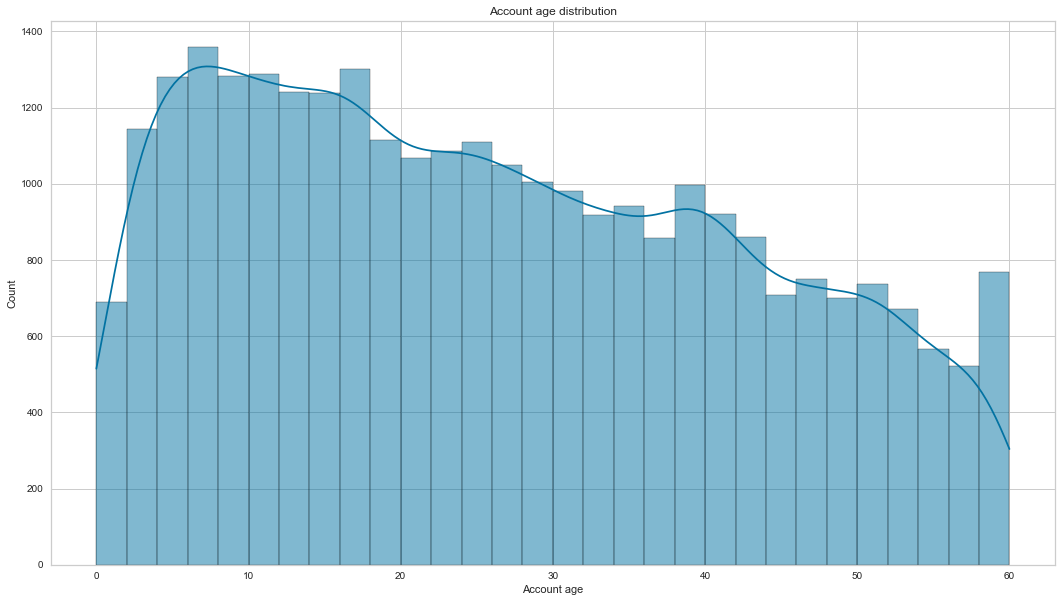

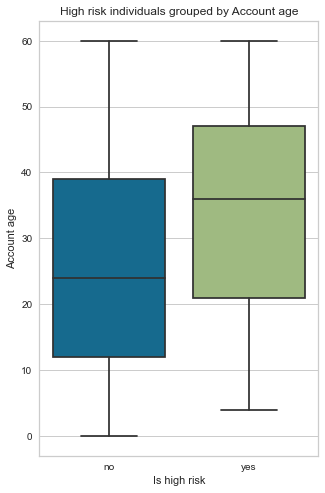

Account age

Most accounts are 26 months old. The account age feature is not normally distributed; it is positively skewed. Another observation is that, on average, bad clients’ accounts are 34 months old vs 26 months old for good clients’ accounts.

gen_info_feat(cc_train_copy,'Account age')

Description:

count 29165.00

mean 26.14

std 16.49

min 0.00

25% 12.00

50% 24.00

75% 39.00

max 60.00

Name: Account age, dtype: float64

**************************************************

Object type:float64

create_box_plot(cc_train_copy,'Account age')

create_hist_plot(cc_train_copy,'Account age', the_bins=30)

- bivariate analysis with target variable

low_high_risk_box_plot(cc_train_copy,'Account age')

Is high risk

0 26.00

1 34.04

Name: Account age, dtype: float64

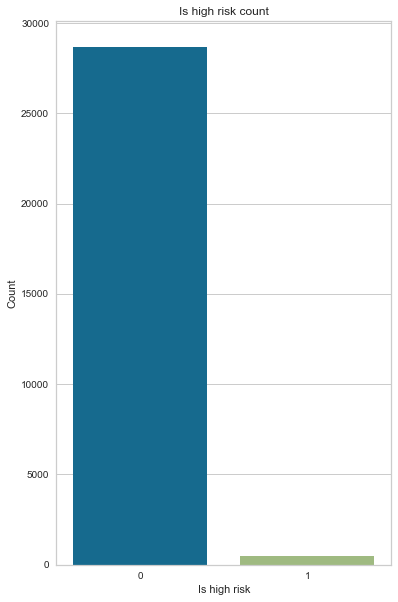

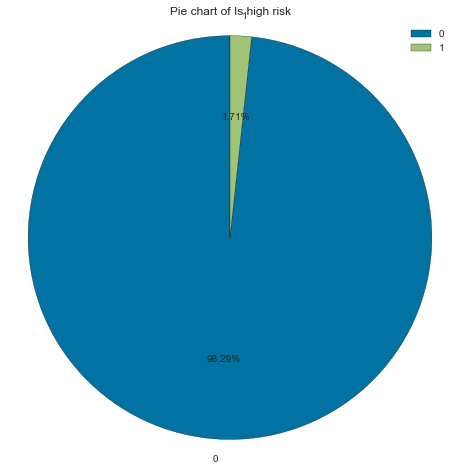

Is high risk (target variable)

Most applicants are good clients (98% of applicants). We have imbalanced data that needs to be balanced using SMOTE before training on a model.

Note: Here, 0 is no and 1 is yes

gen_info_feat(cc_train_copy,'Is high risk')

Description:

count 29165

unique 2

top 0

freq 28666

Name: Is high risk, dtype: int64

**************************************************

Object type:

object

**************************************************

Value count:

Count Frequency (%)

0 28666 98.29

1 499 1.71

create_bar_plot(cc_train_copy,'Is high risk')

create_pie_plot(cc_train_copy,'Is high risk')

Bivariate analysis

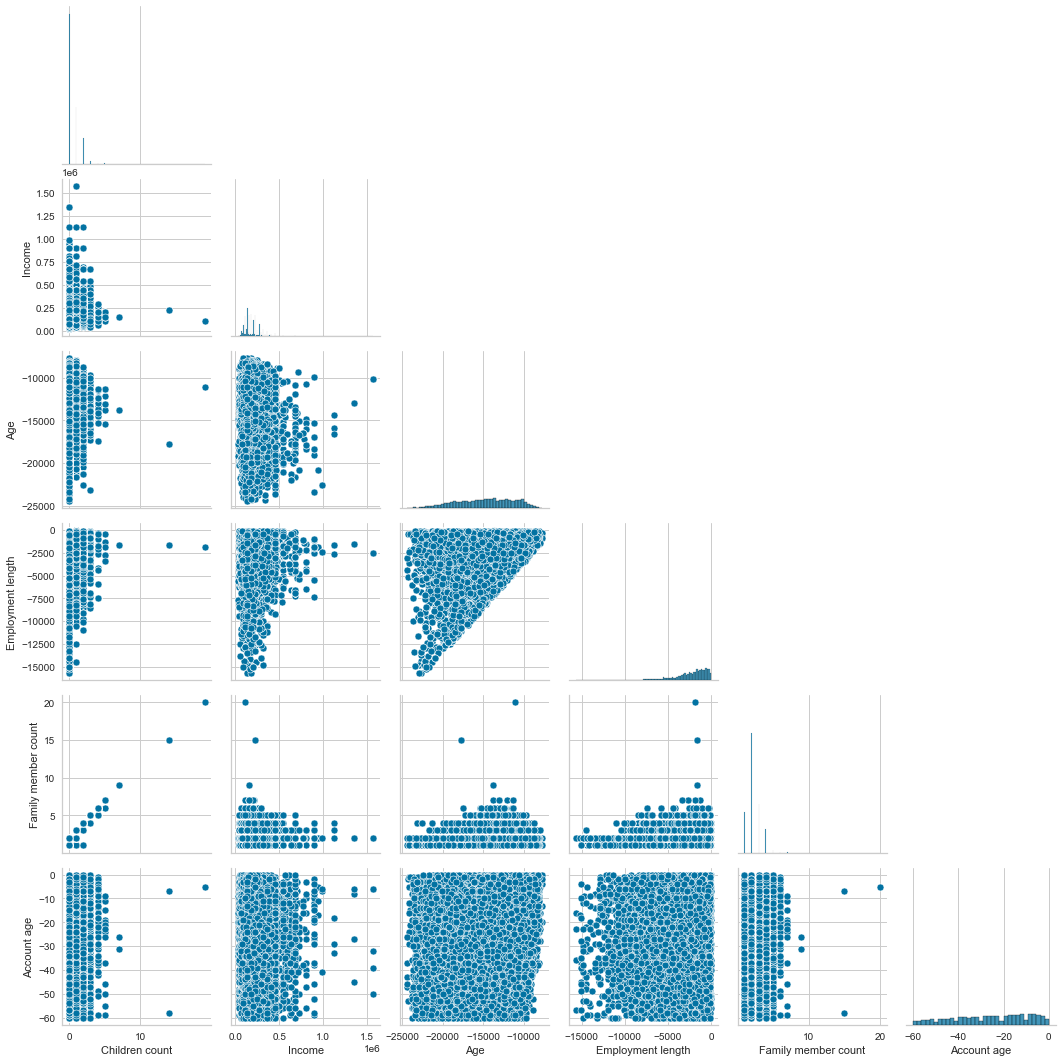

Now that we have finished our univariate analysis let’s look into the bivariate analysis. Bivariate analysis, as the name implies, is the analysis of two features compared with each other. First, we will do a bivariate analysis of numerical features.

Looking at the pairplot (scatter plots of pairwise relationships in a dataset), we can see a positive linear correlation between the family member and the children’s count. It makes sense; the more children someone has, the larger the family member count. It is a multicollinearity problem (two highly correlated features) which is not ideal for training a model. We will need to drop one of them.

Another trend is the Employment length and age. It also makes sense; the longer the employment length, the older someone is.

# drop categorical features, do a pairplot of the remaining feature numerical feature

sns.pairplot(cc_train_copy[cc_train_copy['Employment length'] < 0].drop(['ID','Has a mobile phone', 'Has a work phone', 'Has a phone', 'Has an email','Is high risk'],axis=1),corner=True)

plt.show()

Now let’s look at the two interesting scatter plots.

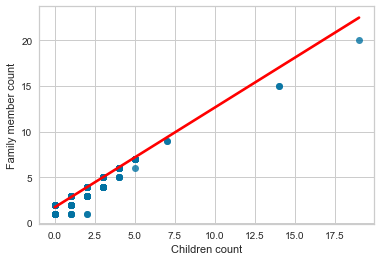

We will start with the family member count vs children count. Of course, the more children a person has, the larger the family count. We added a line of best fit, also called the regression line, and you can read more about it in this blog post here.

sns.regplot(x='Children count',y='Family member count',data=cc_train_copy,line_kws={'color': 'red'})

plt.show()

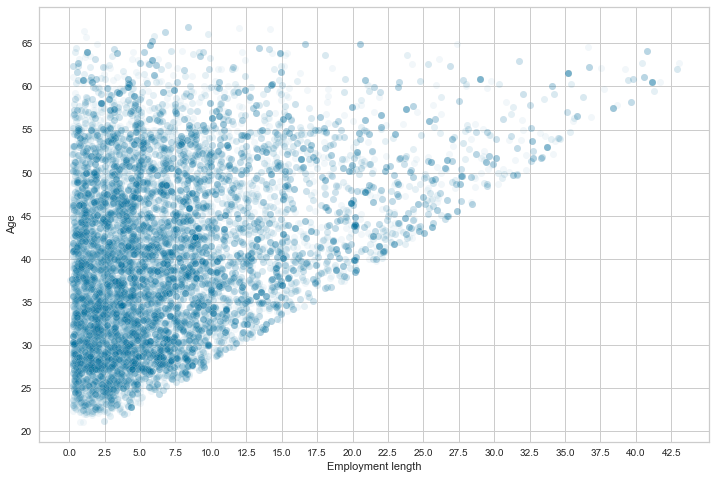

When we compare the employment length and age, the scatterplot shows a trend between the age and the length of employment.

It is shaped like a reversed triangle because the applicants’ age increases with the employment length. You can’t have an employment length that is superior to the age. Right?

y_age = np.abs(cc_train_copy['Age'])/365.25

x_employ_length = np.abs(

cc_train_copy[cc_train_copy['Employment length'] < 0]['Employment length'])/365.25

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(12, 8))

sns.scatterplot(x_employ_length, y_age, alpha=.05)

# change the frequency of the x-axis and y-axis labels

plt.xticks(np.arange(0, x_employ_length.max(), 2.5))

plt.yticks(np.arange(20, y_age.max(), 5))

plt.show()

/Users/sternsemasuka/opt/anaconda3/lib/python3.9/site-packages/seaborn/_decorators.py:36: FutureWarning: Pass the following variables as keyword args: x, y. From version 0.12, the only valid positional argument will be `data`, and passing other arguments without an explicit keyword will result in an error or misinterpretation.

warnings.warn(

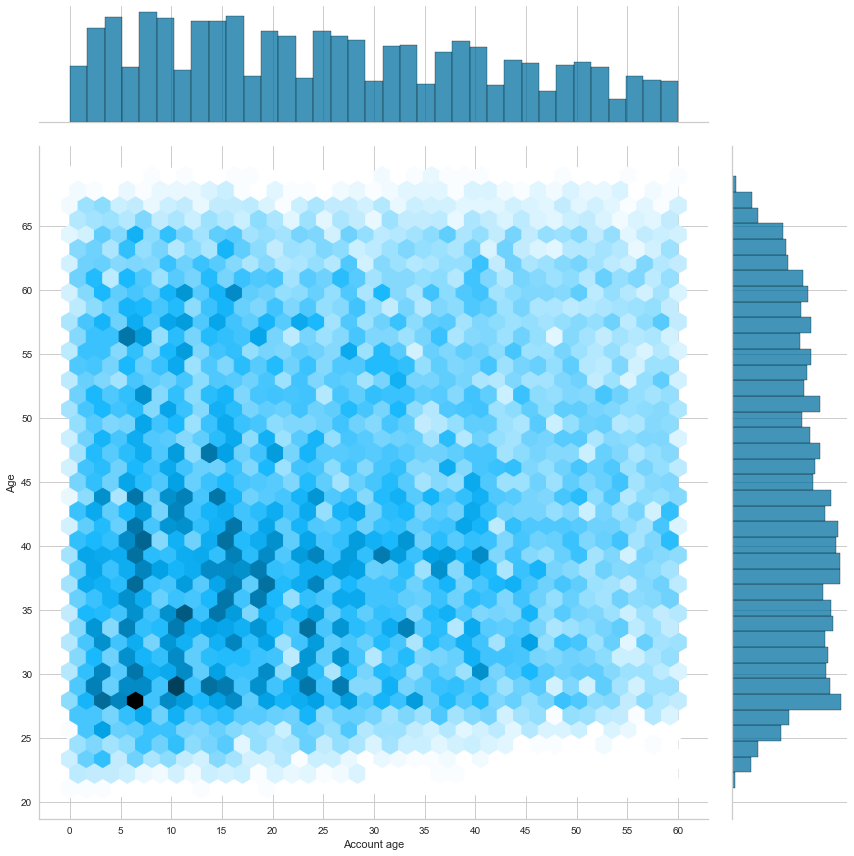

Now comparing account age and applicant age, we can see that most applicants are between 20 and 45 years old and have an account less than 25 months old. This information is deduced from darker blue hexagons (high-density area) between 22 and 43 on the Y axis and between 3 and 28 on the X axis.

sns.jointplot(np.abs(cc_train_copy['Account age']),y_age, kind="hex", height=12)

plt.yticks(np.arange(20, y_age.max(), 5))

plt.xticks(np.arange(0, 65, 5))

plt.ylabel('Age')

plt.show()

/Users/sternsemasuka/opt/anaconda3/lib/python3.9/site-packages/seaborn/_decorators.py:36: FutureWarning: Pass the following variables as keyword args: x, y. From version 0.12, the only valid positional argument will be `data`, and passing other arguments without an explicit keyword will result in an error or misinterpretation.

warnings.warn(

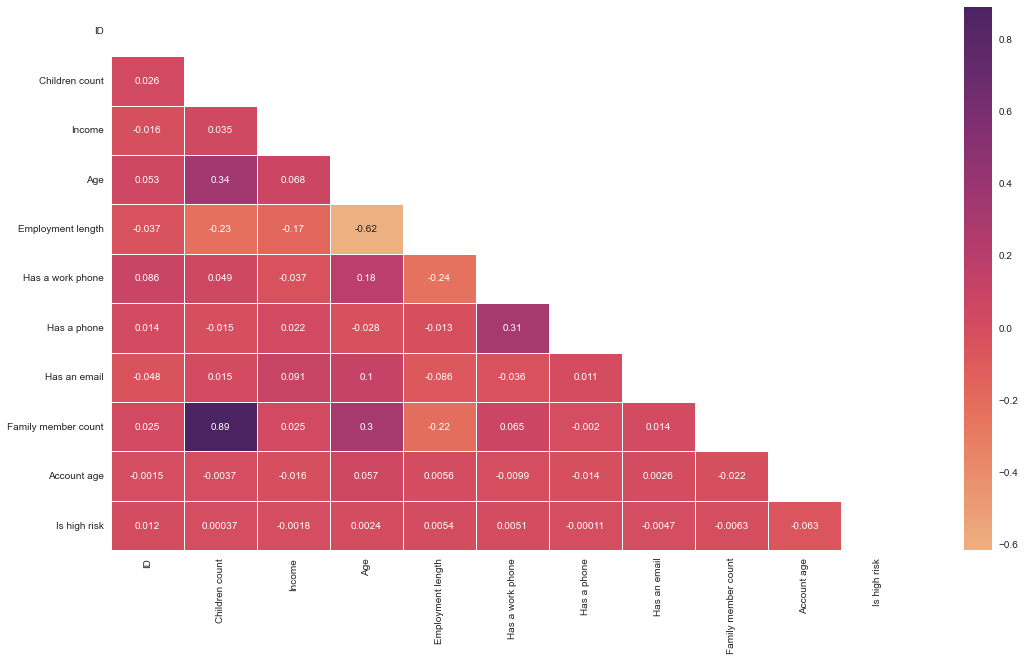

Heatmap

Time to do a correlation between all the numerical features using a heatmap. This heatmap shows the correlation between all the numerical features; the darker the cell, the more correlated the two features are, and the lighter the color, the less correlated the two features.

No feature is correlated with the target feature (Which is high risk). We see a strong correlation (0.89) between family member count and children count, as previously seen with the pairplot (The more children a person has, the larger the family count). Age has some positive correlation (0.30) with the family member count and children count. The older a person is, the most likely they will have a larger family and consequently more children.

Another positive correlation (0.31) is having a phone and having a work phone. We have a slightly positive correlation between age and work phone(0.18); younger people will be less likely to own a work phone. As previously discussed, we also have a negative (-0.62) between employment length and age.

# change the datatype of the target feature to int

is_high_risk_int = cc_train_copy['Is high risk'].astype('int32')

# correlation analysis with heatmap, after dropping the has a mobile phone with the target feature as int

cc_train_copy_corr_no_mobile = pd.concat([cc_train_copy.drop(['Has a mobile phone','Is high risk'], axis=1),is_high_risk_int],axis=1).corr()

# Get the lower triangle of the correlation matrix

# Generate a mask for the upper triangle

mask = np.zeros_like(cc_train_copy_corr_no_mobile, dtype='bool')

mask[np.triu_indices_from(mask)] = True

# Set up the matplotlib figure

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(18,10))

# seaborn heatmap

sns.heatmap(cc_train_copy_corr_no_mobile, annot=True, cmap='flare',mask=mask, linewidths=.5)

# plot the heatmap

plt.show()

ANOVA

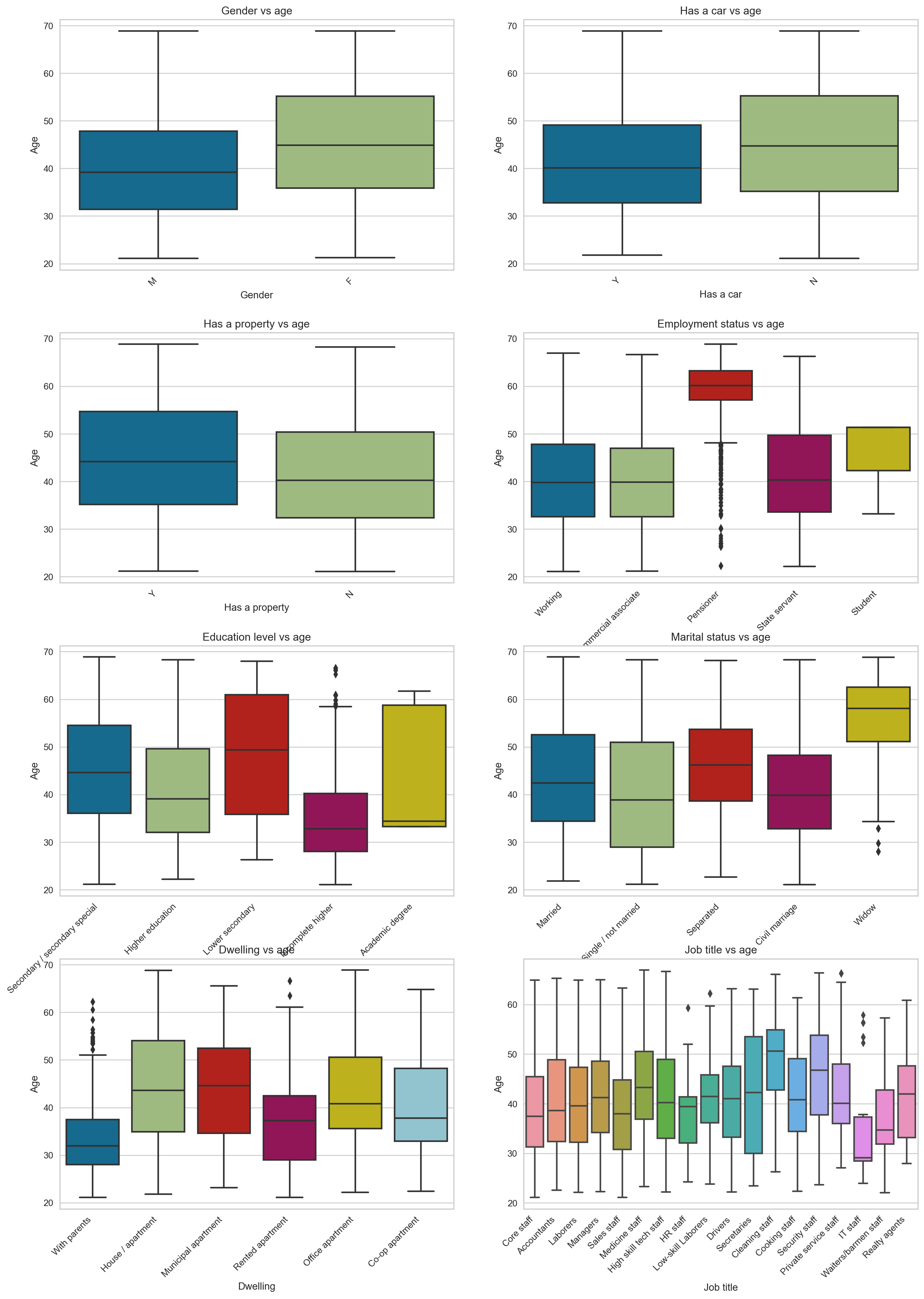

Now, let’s do an ANOVA (analysis of variance) between age and other categorical features.

But before we proceed, what is an ANOVA? ANOVA tells you if there are any statistical differences between the means of two or more independent features (categorical features).

Now, let’s use box plots to compare age’s mean and different categorical features. Female applicants are older than their male counterparts, and those who don’t own a car with property owners tend to be older. Of course, the pensioners are older than those working (We also see that some have pensioned at a young age, those are outliers).

It is also interesting to see that those with an academic degree are generally younger than the other groups. The widows tend to be much older, with some young outliers in their 30s. Unsurprisingly, those who live with their parents tend to be younger, and we also see some outliers here. Lastly, those who work as cleaning staff tend to be older, while those who work in IT tend to be younger.

fig, axes = plt.subplots(4,2,figsize=(15,20),dpi=180)

fig.tight_layout(pad=5.0)

cat_features = ['Gender', 'Has a car', 'Has a property', 'Employment status', 'Education level', 'Marital status', 'Dwelling', 'Job title']

for cat_ft_count, ax in enumerate(axes):

for row_count in range(4):

for feat_count in range(2):

sns.boxplot(ax=axes[row_count,feat_count],x=cc_train_copy[cat_features[cat_ft_count]],y=np.abs(cc_train_copy['Age'])/365.25)

axes[row_count,feat_count].set_title(cat_features[cat_ft_count] + " vs age")

plt.sca(axes[row_count,feat_count])

plt.xticks(rotation=45,ha='right')

plt.ylabel('Age')

cat_ft_count += 1

break

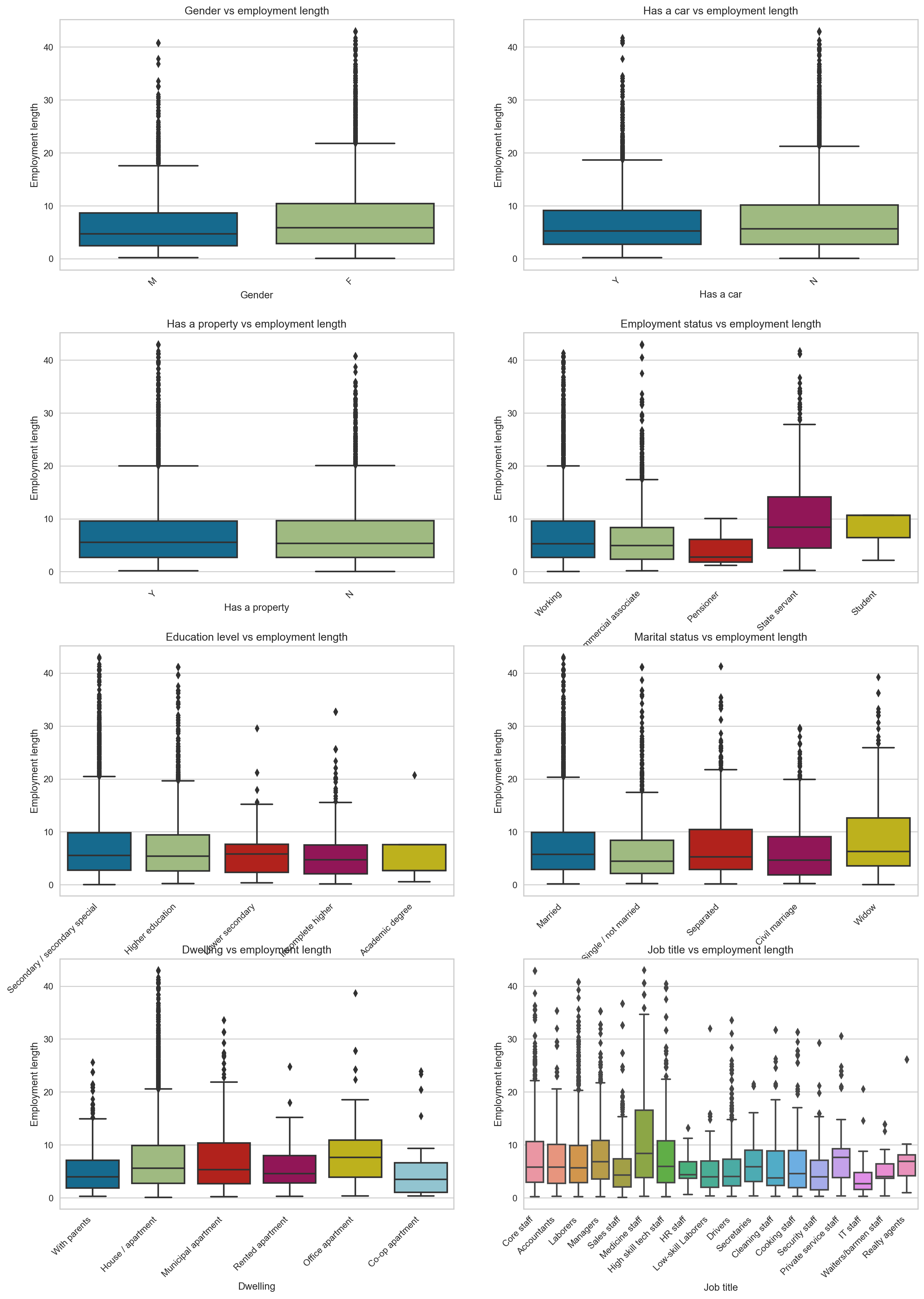

Now let’s turn our attention to employment length versus categorical features. The only interesting observation is that state-employed and medical staff applicants tend to have been employed longer than the rest.

fig, axes = plt.subplots(4,2,figsize=(15,20),dpi=180)

fig.tight_layout(pad=5.0)

for cat_ft_count, ax in enumerate(axes):

for row_count in range(4):

for feat_count in range(2):

sns.boxplot(ax=axes[row_count,feat_count],x=cc_train_copy[cat_features[cat_ft_count]],y=np.abs(cc_train_copy[cc_train_copy['Employment length'] < 0]['Employment length'])/365.25)

axes[row_count,feat_count].set_title(cat_features[cat_ft_count] + " vs employment length")

plt.sca(axes[row_count,feat_count])

plt.ylabel('Employment length')

plt.xticks(rotation=45,ha='right')

cat_ft_count += 1

break

Applicant general profile

After analyzing each feature, we can create a typical credit card applicant profile. Here is the profile:

- Typical profile of an applicant is a Female in her early 40’s, married with a partner and no child. She has been employed for five years with a salary of 157500. She has completed her secondary education. She does not own a car but owns a property (a house/ apartment). Her account is 26 months old.

- Age and income do not have any effects on the target variable

- Those flagged as bad clients tend to have a shorter employment length and older accounts. They also constitute less than 2% of total applicants.

- Most applicants are 20 to 45 years old and have an account that is 30 months old or less.

3. Prepare the data

Using EDA, here is a list of all the transformations that need to be done on each feature:

ID:

- Drop the feature

Gender:

- One hot encoding

Age:

- Min-max scaling

- Fix skewness

- Absolute values and divide by 365.25

Marital status:

- One hot encoding

Family member count

- Fix outliers

Children count

- Fix outliers

- Drop feature

Dwelling type

- One hot encoding

Income

- Remove outliers

- Fix skewness

- Min-max scaling

Job title

- One hot encoding

- Impute missing values

Employment status:

- One hot encoding

Education level:

- Ordinal encoding

Employment length:

- Remove outliers

- Min-max scaling

- Absolute values and divide by 365.25

- change days of employment of retirees to 0

Has a car:

- Change it to numerical

- One-hot encoding

Has a property:

- Change it to numerical

- One-hot encoding

Has a mobile phone:

- Drop feature

Has a work phone:

- One-hot encoding

Has a phone:

- One-hot encoding

Has an email:

- One-hot encoding

Account age:

- Drop feature

Is high risk(Target):

- Change the data type to numerical

- balance the data with SMOTE

Data Cleaning

Here we are creating a class to handle outliers. But why do we have to remove the outliers?

Outliers are data points that differ significantly from other observations in the dataset. Outliers can spoil and mislead the training process resulting in longer training times, less accurate models and ultimately poorer results, which means that outliers must remove from the dataset.

This class will remove outliers more or less than 3 inter-quantile ranges away from the mean. This class will be the first class in the scikit-learn Pipeline to call.

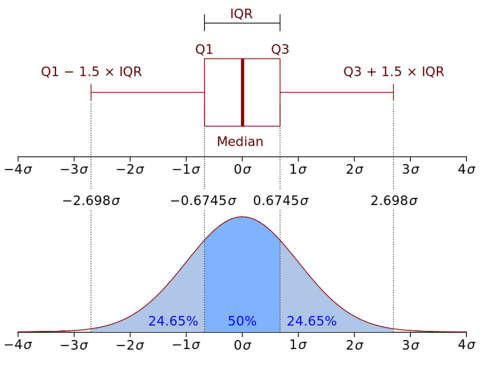

Note: Refer to this picture below to understand IQR. In the image below, 1.5 IQR is used; in our case, we use 3 IQR, which is more sensitive to extreme outliers than 1.5 IQR.

Image credit: Research gate

class OutlierRemover(BaseEstimator, TransformerMixin):

def __init__(self,feat_with_outliers = ['Family member count','Income', 'Employment length']):

# initializing the instance of the object

self.feat_with_outliers = feat_with_outliers

def fit(self,df):

return self

def transform(self,df):

# check if the feature in part of the dataset's features

if (set(self.feat_with_outliers).issubset(df.columns)):

# 25% quantile

Q1 = df[self.feat_with_outliers].quantile(.25)

# 75% quantile

Q3 = df[self.feat_with_outliers].quantile(.75)

IQR = Q3 - Q1

# keep the data within 3 IQR only and discard the rest

df = df[~((df[self.feat_with_outliers] < (Q1 - 3 * IQR)) |(df[self.feat_with_outliers] > (Q3 + 3 * IQR))).any(axis=1)]

return df

else:

print("One or more features are not in the dataframe")

return df

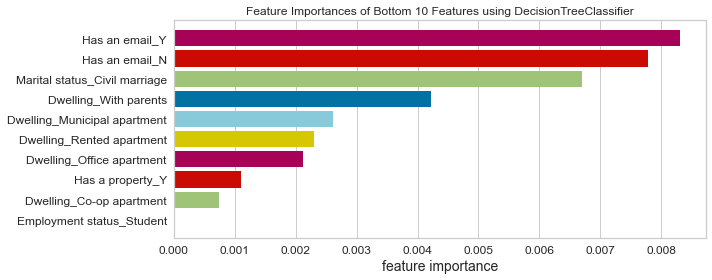

Feature selection

Next is feature selection; here, we will drop the features that we judge are not useful in our prediction. Note this is not a feature selection based on the model coefficients or feature importance; it is purely based on logic.

The features to be dropped are ID, has a mobile phone, children count, job title, account age.

Now the next question is, why are we dropping these features?

- ID: ID is not helpful for prediction, it helped us when we were merging the two datasets, but after that, there is no need to keep it.

- Has a mobile phone: Since everyone has a mobile phone, this feature does not inform us about anything and is useless for the model.

- Children count: is highly correlated with Family member count, and to avoid multicollinearity, we will drop it.

- Job title: Has some missing values and the count of each category is not very different to justify using the mode to fill the missing values. So we drop it.

- Account age: Because Account age is used to create the target, reusing it will make our model overfit. Plus, this information is unknown while applying for a credit card and is not a predictor feature.

class DropFeatures(BaseEstimator,TransformerMixin):

def __init__(self,feature_to_drop = ['ID','Has a mobile phone','Children count','Job title','Account age']):

self.feature_to_drop = feature_to_drop

def fit(self,df):

return self

def transform(self,df):

if (set(self.feature_to_drop).issubset(df.columns)):

# drop the list of features

df.drop(self.feature_to_drop,axis=1,inplace=True)

return df

else:

print("One or more features are not in the dataframe")

return df

Feature engineering

This class will convert the features that use days (Employment length, Age) to absolute value because we can’t have negative days of employment.

class TimeConversionHandler(BaseEstimator, TransformerMixin):

def __init__(self, feat_with_days = ['Employment length', 'Age']):

self.feat_with_days = feat_with_days

def fit(self, X, y=None):

return self

def transform(self, X, y=None):

if (set(self.feat_with_days).issubset(X.columns)):

# convert days to absolute value using NumPy

X[['Employment length','Age']] = np.abs(X[['Employment length','Age']])

return X

else:

print("One or more features are not in the dataframe")

return X

The following class will convert the employment length of retirees (set to 365243) to 0 so that it is not considered an outlier.

class RetireeHandler(BaseEstimator, TransformerMixin):

def __init__(self):

pass

def fit(self, df):

return self

def transform(self, df):

if 'Employment length' in df.columns:

# select rows with an employment length is 365243, which corresponds to retirees

df_ret_idx = df['Employment length'][df['Employment length'] == 365243].index

# set those rows with value 365243 to 0

df.loc[df_ret_idx,'Employment length'] = 0

return df

else:

print("Employment length is not in the dataframe")

return df

Using the cubic root transformation, this class will reduce income and age distribution skewness. Skewed features negatively affect our predictive model’s performance, and machine learning models perform better with normally distributed data.

class SkewnessHandler(BaseEstimator, TransformerMixin):

def __init__(self,feat_with_skewness=['Income','Age']):

self.feat_with_skewness = feat_with_skewness

def fit(self,df):

return self

def transform(self,df):

if (set(self.feat_with_skewness).issubset(df.columns)):

# Handle skewness with cubic root transformation

df[self.feat_with_skewness] = np.cbrt(df[self.feat_with_skewness])

return df

else:

print("One or more features are not in the dataframe")

return df

This class will change 1 to the character “Y” and 0 to “N,” which will be more comprehensive when we do a one-hot encoding for these features Has a work phone, Has a phone, Has an email.

class BinningNumToYN(BaseEstimator, TransformerMixin):

def __init__(self,feat_with_num_enc=['Has a work phone','Has a phone','Has an email']):

self.feat_with_num_enc = feat_with_num_enc

def fit(self,df):

return self

def transform(self,df):

if (set(self.feat_with_num_enc).issubset(df.columns)):

# Change 0 to N and 1 to Y for all the features in feat_with_num_enc

for ft in self.feat_with_num_enc:

df[ft] = df[ft].map({1:'Y',0:'N'})

return df

else:

print("One or more features are not in the dataframe")

return df

This class will do one-hot encoding on the categorical features, but also this class will keep the names of the features. We want to keep the feature names instead of an array without names (default) because the feature names will be used for feature importance.

class OneHotWithFeatNames(BaseEstimator,TransformerMixin):

def __init__(self,one_hot_enc_ft = ['Gender', 'Marital status', 'Dwelling', 'Employment status', 'Has a car', 'Has a property', 'Has a work phone', 'Has a phone', 'Has an email']):

self.one_hot_enc_ft = one_hot_enc_ft

def fit(self,df):

return self

def transform(self,df):

if (set(self.one_hot_enc_ft).issubset(df.columns)):

# function to one-hot encode the features

def one_hot_enc(df,one_hot_enc_ft):

# instantiate the OneHotEncoder object

one_hot_enc = OneHotEncoder()

# fit the dataframe with the features we want to one-hot encode

one_hot_enc.fit(df[one_hot_enc_ft])

# get output feature names for transformation.

feat_names_one_hot_enc = one_hot_enc.get_feature_names_out(one_hot_enc_ft)

# change the one hot encoding array to a dataframe with the column names

df = pd.DataFrame(one_hot_enc.transform(df[self.one_hot_enc_ft]).toarray(),columns=feat_names_one_hot_enc,index=df.index)

return df

# function to concatenate the one hot encoded features with the rest of the features that were not encoded

def concat_with_rest(df,one_hot_enc_df,one_hot_enc_ft):

# get the rest of the features that are not encoded

rest_of_features = [ft for ft in df.columns if ft not in one_hot_enc_ft]

# concatenate the rest of the features with the one hot encoded features

df_concat = pd.concat([one_hot_enc_df, df[rest_of_features]],axis=1)

return df_concat

# call the one_hot_enc function and stores the dataframe in the one_hot_enc_df variable

one_hot_enc_df = one_hot_enc(df,self.one_hot_enc_ft)

# returns the concatenated dataframe and stores it in the full_df_one_hot_enc variable

full_df_one_hot_enc = concat_with_rest(df,one_hot_enc_df,self.one_hot_enc_ft)

return full_df_one_hot_enc

else:

print("One or more features are not in the dataframe")

return df

This class will convert the education level to an ordinal encoding. Here we use ordinal encoding instead of one-hot encoding because we know that the education level is ranked (University is higher than primary school).

class OrdinalFeatNames(BaseEstimator,TransformerMixin):

def __init__(self,ordinal_enc_ft = ['Education level']):

self.ordinal_enc_ft = ordinal_enc_ft

def fit(self,df):

return self

def transform(self,df):

if 'Education level' in df.columns:

# instantiate the OrdinalEncoder object

ordinal_enc = OrdinalEncoder()

df[self.ordinal_enc_ft] = ordinal_enc.fit_transform(df[self.ordinal_enc_ft])

return df

else:

print("Education level is not in the dataframe")

return df

This class will scale the feature using min-max scaling while keeping the feature names. You may ask why we have to scale. Well, some of the numerical features range from 0 to 20 (Family member count) while others range from 27000 to 1575000 (Income), so this means that some machine learning algorithms will weight the features with big numbers more than the feature with smaller numbers which should not be the case. So scaling all the numerical feature on the same scale (0 to 1) solve this issue.

class MinMaxWithFeatNames(BaseEstimator,TransformerMixin):

def __init__(self,min_max_scaler_ft = ['Age', 'Income', 'Employment length']):

self.min_max_scaler_ft = min_max_scaler_ft

def fit(self,df):

return self

def transform(self,df):

if (set(self.min_max_scaler_ft).issubset(df.columns)):

# instantiate the MinMaxScaler object

min_max_enc = MinMaxScaler()

# fit and transform on a scale 0 to 1

df[self.min_max_scaler_ft] = min_max_enc.fit_transform(df[self.min_max_scaler_ft])

return df

else:

print("One or more features are not in the dataframe")

return df

This class will change the data type of the target variable to numerical as it is an object data type even though it is 0 and 1’s (0 and 1’s expressed as strings)

class ChangeToNumTarget(BaseEstimator,TransformerMixin):

def __init__(self):

pass

def fit(self,df):

return self

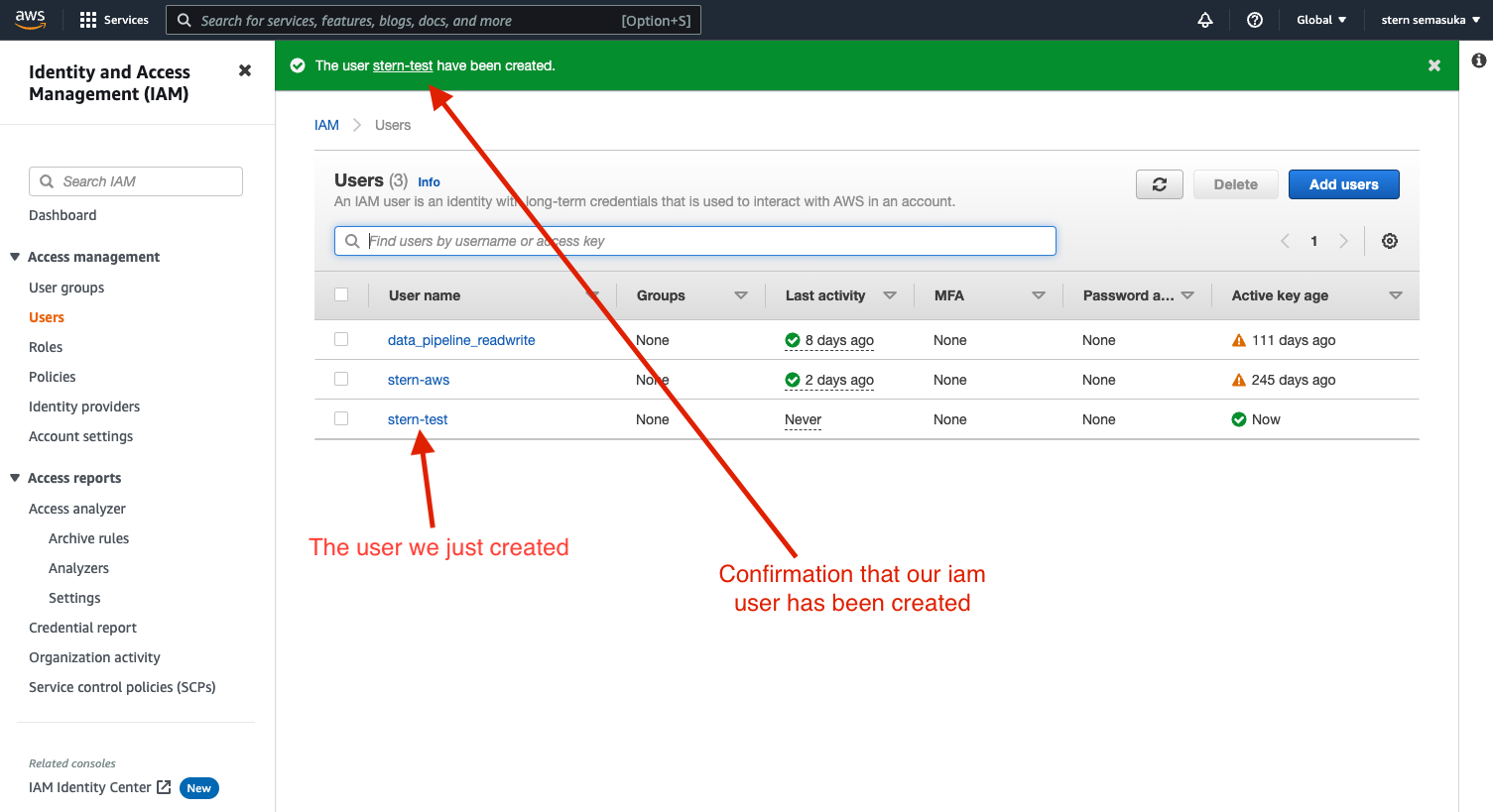

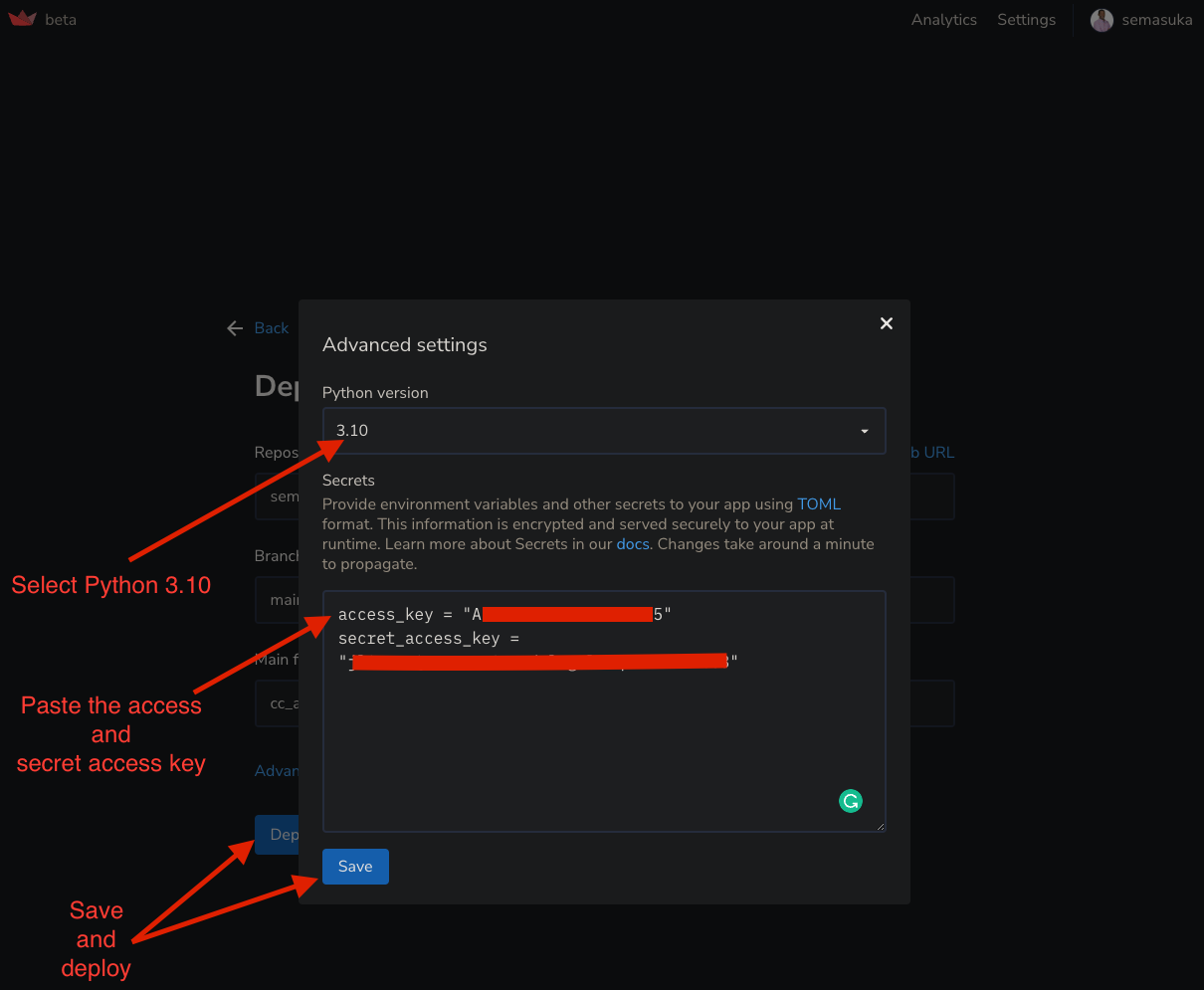

def transform(self,df):